Understanding the Chaos: Inside the 2025 Immigration Enforcement Surge

With immigration arrests surging in 2025, confusion about law enforcement actions and what’s permissible is at an all-time high. We help clear the air.

Produced in partnership with Organized Power in Numbers.

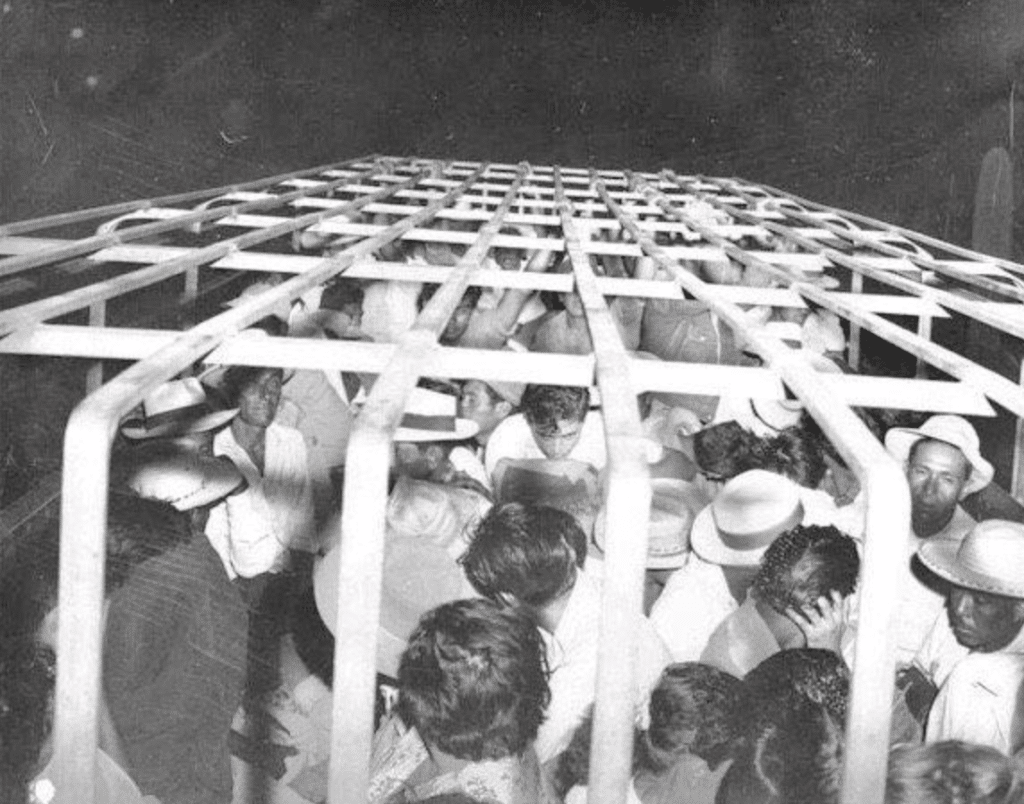

Immigration enforcement in the U.S. has entered one of its most racially charged and aggressive phases since Operation Wetback in 1954, when federal agents carried out mass deportations of Mexican and Mexican American families in what the government stated was an effort to curb illegal immigration and protect “American jobs.” In the first half of 2025 alone, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detained more than 100,000 individuals. According to the latest available data, ICE held 59,762 people in detention as of September 2025, and 42,755 or 71.5% of detainees, have no criminal conviction. This is in direct contrast to the campaign promises Trump made, assuring the public that enforcement would target only those with criminal histories.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) shared that over 2 million people have been “removed or self-deported” as of September 2025, and stated they are on pace to deport approximately 600,000 individuals by year’s end. This overall increase in immigration enforcement activity has sparked widespread confusion, fear, and legal questions, especially for Latinos who remain disproportionately targeted.

Amid this escalation, community organizations have stepped up to provide clarity and protection. Organized Power in Numbers (OPIN), an organization that brings together working people across the South and Southwest to push for workers’ rights, housing justice, and a government that puts everyday people over billionaires, for example, trains communities on how to prepare and respond during encounters with immigrations, particularly in the workplace.

Founded by Neidi Dominguez Zamorano, OPIN is bridging modern digital strategy and classic community organizing. Whether that’s challenging abusive workplace practices and training immigrant and non-immigrant workers on their rights, advocating for housing protections, or moving masses of working people into action together to demand their tax dollars be spent on their communities, their work highlights that rights are most powerful when exercised collectively.

With federal, state, and local agencies often working in overlapping ways, many are uncertain about what each authority is legally permitted to do. While the Trump administration regularly pushes the boundaries of constitutional protections, some local and state leaders are pushing back by attempting to keep their law enforcement agencies responsive to the needs of their communities. This leads to even more confusion in an already chaotic environment where Border Patrol and ICE agents are openly defying the historically accepted practice of clear identification as law enforcement officers, unless working undercover.

It also creates more questions. What agencies are doing what? What powers do they legally have, and what do you need to know if you’re approached in the street, at work, in your car, or at home?

Who’s Who: ICE, Police, CBP, and the Military

Over a dozen different agencies and entities are involved in immigration administrative operations, judicial proceedings, enforcement, public safety, or military operations, but their powers vary significantly.

Federal Agencies Currently Involved in Immigration Removals: ICE, ERO, HSI, DSS, Border Patrol, and FBI

ICE enforces civil immigration laws inside the U.S. through its two main divisions: Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) and Homeland Security Investigations (HSI). Recently, agencies that have historically not been involved with removal field work, such as the U.S. Border Patrol and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), have also been assigned to conduct deportation arrests.

Border Patrol, traditionally responsible for enforcing immigration laws at and near the nation’s borders, has expanded its operations deeper into the interior. According to a June 2025 Associated Press report, Border Patrol agents have been increasingly deployed to assist ICE in carrying out at-large arrests across the country. While ICE continues to lead civil immigration enforcement, Border Patrol agents are now conducting field operations, workplace raids, and transportation-hub inspections in collaboration with ERO teams, blurring the line between border and interior enforcement.

The FBI has also increasingly participated in joint immigration-enforcement operations in 2024–25, especially those involving national-security risks, organized crime and document or visa fraud. Public reporting shows a major shift: By October 2025, media reporting based on data obtained by Sen. Mark Warner indicated that around 23% of FBI agents were reassigned to support immigration enforcement, assisting ICE and DHS in locating and apprehending non-citizens subject to removal.

These officers and agents may make arrests, conduct raids, and detain individuals they believe are in the country unlawfully. While ICE officers can question individuals about their immigration status, they generally need reasonable suspicion of an immigration violation to briefly stop someone, and probable cause or a warrant to make an arrest.

Most ICE warrants are administrative (Form I-200/I-205) signed by DHS officials, not judges, and don’t authorize entry into a private home without consent or a judicial warrant. ICE officers typically drive unmarked vehicles, wear masks, and may work in plain clothes or wear black bulletproof vests labeled “POLICE,” “ICE,” or “Federal Agent,” often without visible badge numbers or name tags. While agents are issued both a badge (a physical emblem identifying them as law enforcement) and credentials (an official ID card verifying their authority and agency), federal law doesn’t explicitly require them to display either during every encounter, so practices vary by agency and assignment, a lack of transparency that critics say reduces accountability.

ICE agents have now been documented in thousands of videos using deceptive or outright violent and aggressive tactics to gain entry into homes, workplaces, and vehicles, pretending to be local police or probation officers. These tactics are known as “ruses,” and they’re officially sanctioned, making it easier for agents to gain access to someone’s home or obtain information without revealing they’re ICE, which prevents immigrants from exercising their right to refuse them entry to their homes or answer their questions. Courts have historically tolerated some deception by law enforcement, but critics such as the ACLU argue that ICE ruses are a violation of the Fourth Amendment, which protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures.

Despite evidence of ongoing constitutional-rights violations by federal agents, legal advocates stress that it’s still very important to assert your rights and to document the encounter so that any violations can be preserved for future legal claims. Organizations like the ACLU, Immigrant Justice, Immigrant Defense Justice, and the American Immigration Lawyers Association all advise to clearly state that you choose to remain silent, ask whether you are free to go, refuse consent to entry if no judicial warrant is shown, request an attorney, and immediately record or write down the agents’ names, badge numbers, the date/time and what they said or did.

The State Department’s Diplomatic Security Service (DSS) is also involved in immigration enforcement. DSS has had authority to investigate and make arrests in passport and visa fraud (such as forged or stolen passports, false visa applications, identity theft, and marriage or document fraud), but its operational involvement in immigration enforcement expanded significantly. In recent years, particularly in the 2020s, the role of DSS in cooperation with the DHS and U.S. immigration-law enforcement agencies has expanded.

For example, in early 2025 a DHS memorandum deputized up to 600 DSS agents to perform immigration-officer functions to locate and apprehend people in the U.S. in violation of immigration regulations. While detailed public records of joint operations with HSI/CBP from the mid-2010s onward are limited, the trend toward closer inter-agency work and broader use of DSS in immigration-related enforcement is evident.

State and Local Police

The primary role of state and local police is to enforce state and local laws, maintain public safety, and serve the community. Unlike federal immigration agents, local officers operate under state authority, typically using marked patrol vehicles and standard uniforms, badges, and department insignia. They may work in plain clothes without visual identifiers, and, while there’s no federal law that requires it, most police departments have internal policies that require them to present identification when asked.

The role of state and local police doesn’t include the enforcement of federal immigration law unless they have a 287(g) agreement with ICE. 287(g) agreements allow the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to deputize certain trained local or state officers to perform limited federal immigration enforcement functions under ICE supervision, such as verifying immigration status or issuing detainers.

Outside these agreements, local officers generally can’t question, detain, or arrest individuals solely based on immigration status or civil immigration violations. Many departments explicitly prohibit cooperation with ICE on these grounds, especially in sanctuary jurisdictions. Even in non-sanctuary areas, courts have found that honoring ICE detainer requests without a judicial warrant can violate the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unlawful detention.

The Military and National Guard

Under the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, active-duty U.S. military generally may not perform civilian law-enforcement functions (like arrests or searches) unless expressly authorized by law; their domestic roles are typically logistical and protective support, not enforcement-based. In 2025, National Guard deployments tied to immigration operations became the subject of ongoing litigation in California, where testimony indicated Guard soldiers accompanied ICE on a large share of missions.

Any detention by military personnel has been described as tightly limited, such as brief custody on federal installations with prompt handoff to civilian authorities. In Los Angeles after early-June raids, active-duty Marines were restricted to defending federal property and personnel, while Guard forces were used chiefly for security and force protection around operations. At or near the border, military and Guard units primarily provide surveillance, engineering, transportation, and other support to CBP rather than carrying out immigration enforcement themselves.

To date, there are very few exceptions where military personnel have been legally authorized to detain individuals in immigration contexts. The most notable example is the 2025 authorization allowing U.S. military personnel, including the Texas National Guard, to temporarily detain and search migrants who trespass on areas designated as military installations such as the New Mexico National Defense Area. The government asserts this authority under national defense exceptions, but its scope remains contested and under litigation.

Additionally, the Department of Defense (DoD), under U.S. Northern Command, has been authorized to provide logistical and, in limited cases, temporary detention support in designated border zones. While the military isn’t engaged in routine immigration removals, this change marks one of the most significant expansions of military‐adjacent detention authority at the border.

CBP, USCIS and USMS

CBP operates primarily at and near borders, airports, and ports of entry. Its mission is to secure the borders while facilitating lawful trade and travel. CBP agents are authorized to question, detain, and inspect individuals and goods entering or leaving the country. They also conduct certain enforcement activities such as roving patrols, highway checkpoints, and bus or train inspections within up to 100 miles from any U.S. land or maritime border. At fixed checkpoints, CBP may briefly question travelers about citizenship without individualized suspicion, but searches still require consent or probable cause.

CBP doesn’t operate deep inside the U.S. as ICE does and their powers aren’t unlimited. Agents must still have reasonable suspicion to stop and question individuals and probable cause (or consent) to conduct searches or arrests. Courts have repeatedly held that the Fourth Amendment applies within the border zone, even though certain exceptions exist at actual ports of entry.

Within CBP, the Office of Field Operations (OFO) also conducts removals at official ports of entry through expedited removal and repatriation processes. OFO officers are often the first to process deportations for people denied entry or apprehended during secondary inspections at airports and land crossings.

On the other hand, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is a separate agency under the DHS, primarily responsible for processing applications for immigration benefits like green cards, DACA renewals, asylum requests, and citizenship applications, not for immigration enforcement or arrests.

It has historically functioned as a benefits-adjudication agency rather than a law-enforcement body. However, under a final rule published in September 2025, USCIS will now deploy designated “special agents” who are authorized (for the first time in USCIS’s existence) to make arrests, carry firearms, execute search and arrest warrants, and perform investigations related to immigration-benefit fraud, national security risks, or threats to public safety. While USCIS remains responsible for benefits processing, this regulatory change marks a major expansion of its role into enforcement functions.

The U.S. Marshals Service (USMS), which is part of the Department of Justice (DOJ), plays a custodial and logistical role in immigration enforcement. Marshals don’t conduct immigration raids, but they detain, transport, and transfer individuals charged with federal immigration crimes such as illegal re-entry, document fraud, or human smuggling.

Through the Justice Prisoner and Alien Transportation System (JPATS), the Marshals move thousands of noncitizens each year between federal courts, detention centers, and ICE custody. Once criminal proceedings conclude, they coordinate directly with ERO for the individual’s transfer or removal. In this way, the Marshals provide the connective link between the criminal justice system and the civil immigration enforcement apparatus.

Immigrants’ Rights Guaranteed Under the Constitution

Immigrants in the U.S., regardless of status, have rights guaranteed under the Constitution. “A permanent resident and a non-permanent resident, somebody on let’s say an H-1B visa or some other type of temporary visa […] has due process rights,” stated David Leopold, former president and general counsel of the American Immigration Lawyers Association. “Everybody is covered by the United States Constitution. Everybody’s protected by the United States Constitution inside the United States,” he concluded.

In any situation, whether that’s at home or on the street, if they’re approached by immigration enforcement agents or suspected immigration enforcement agents, immigrants have the following rights:

- Right to ask for identification. No law requires agents to show ID in every encounter, but immigrants can ask. If they refuse and have no judicial warrant, immigrants generally don’t have to comply.

- Right to ask to see a warrant. Verify whether it’s judicial (signed by a judge) or administrative (Form I-200/I-205). Administrative warrants don’t authorize entry into a home. Ask them to slide it under the door or show it through a window.

- Right to remain silent. Immigrants can say: “I choose to remain silent.” They don’t have to answer questions about immigration status or country of origin. In some states where there are “stop and identify” statutes, immigrants may be required to provide their name, but these laws generally apply only when there’s reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

- Right to refuse consent to search. Agents can’t search people, cars, or homes without consent or a judicial warrant.

- Right to refuse identification. Non-citizens 18 and over must carry registration documents and may be asked to show them to immigration officers. U.S. citizens aren’t required to carry ID unless state “stop-and-identify” laws apply.

In vehicles: Drivers must show license, registration, and insurance when lawfully stopped. Passengers generally don’t have to show ID unless there’s reasonable suspicion or a valid stop-and-identify law. Vehicle searches require probable cause, consent, or an exception like exigent circumstances. If agents forcibly enter a vehicle without a judicial warrant, probable cause, or exigent circumstances, it may be unlawful and subject to challenge in court.

At checkpoints or border zones: Immigrants must stop if directed, but they can ask if they’re free to go. Agents can briefly ask about citizenship, but can’t detain them longer than necessary without cause.

- Right to speak to legal counsel. Immigrants have the right to speak to a lawyer before answering questions or signing documents, but in most immigrant detention cases, they aren’t entitled to free legal counsel. Detainees would still have to pay for their own lawyer

- Right to due process. Immigrants have the right to a fair hearing before being deprived of “life, liberty, or property,” and they also have the right to challenge their detention or removal in court.

- Right to document the encounter. Immigrants, regardless of status, are legally allowed to record or photograph immigration enforcement agents as long as they don’t interfere with their activities.

- Immigrants also have the right to leave if they’re not being detained or arrested. They can ask, “Am I being arrested or detained?” If the answer is no, they’re free to leave calmly, whether they’re on foot or in a car. If the answer is yes, they can exercise their right to remain silent and ask to speak to a lawyer.

Knowing your rights as a person in the U.S. is essential, but exercising those rights is easier when credible tools, training, and community support are available. Bilingual KYR cards provide short, accessible information on what to say, when to say it, and how to invoke rights safely.

De-escalation guides add another layer, providing practical advice on how to manage fear responses and stay grounded during stressful situations, allowing individuals to assert their rights without confrontation. Community training takes it a step further by teaching participants how to canvas their community to prepare people in case of ICE raids, acknowledging that the best defense is a good offense.

Broader Implications

The sharp increase in enforcement actions has prompted renewed scrutiny of civil rights protections in immigrant communities. The blurred lines between ICE, local police, and military support raise concerns about dangerous gray zones that compromise constitutional safeguards for immigrant communities.

As policy debates escalate, knowing one’s rights remains the first line of defense.