Los Angeles Rebuilds: Are Latinos Being Left Behind in the Recovery?

Los Angeles is rebuilding, but at what cost to the workers doing the heavy lifting?

The aftermath of the Eaton and Palisades fires that started raging on January 7, 2025, has left Los Angeles facing one of the largest rebuilding efforts in its history. Estimates of economic loss reach $250 billion. While city officials move forward with recovery plans, attention is turning to the workforce responsible for reconstructing thousands of homes and businesses.

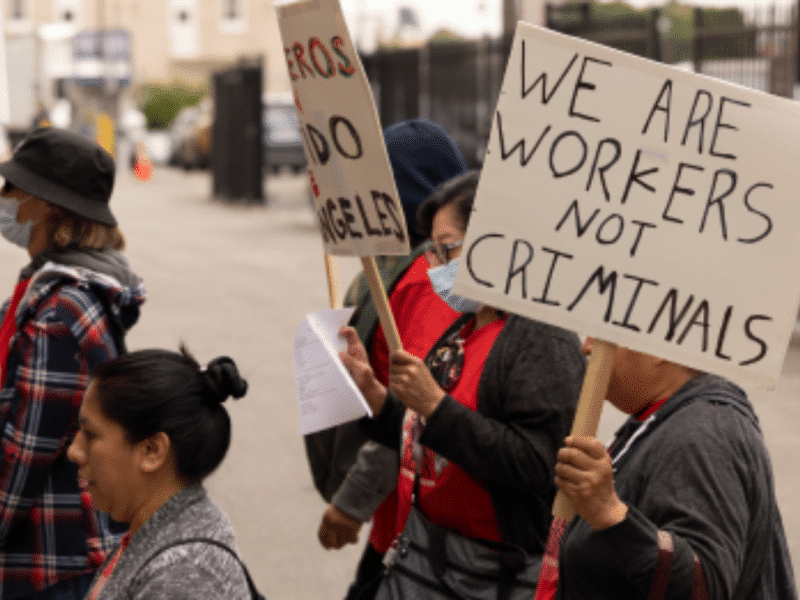

With Latinos accounting for more than 80% of the construction workforce in Los Angeles, their role in the city’s recovery is undeniable. However, disparities in compensation, safety concerns, and fears of immigration enforcement are casting uncertainty over those who will do the work of rebuilding the city.

The Scale of Recovery Efforts

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass has described the city’s post-fire recovery operation as the largest in its history. Over a month after the fires, inspectors have assessed more than 15,000 structures, with over 6,800 completely destroyed. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has also removed hazardous debris from approximately 1,500 properties while local, state, and federal agencies coordinate the next phase of debris removal. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has begun clearing properties where owners have opted into the federal debris removal program. Officials estimate that hazardous waste operations will be completed by the end of February.

While the response has been swift, disparities in the rebuilding effort have sparked controversy. Mayor Bass faced backlash after it was revealed that Steve Soboroff, appointed as the city’s chief recovery officer, was initially set to receive $500,000 for 90 days of work, with another official, Randy Johnson, to receive $250,000. Following public criticism, both officials agreed to work without pay. Despite this adjustment, the news has raised concerns about how recovery funds are being allocated and whether the financial burden of rebuilding is being distributed equitably.

By contrast, the average annual salary for construction workers in Los Angeles ranges between $35,792 and $47,520. Workers and advocates have expressed concerns that while high-profile figures in recovery efforts were set to receive hundreds of thousands of dollars, many construction workers will continue earning low wages under difficult conditions.

The Latino Workforce: Essential Yet Overlooked

Latino construction workers, who make up 84% of the region’s construction workforce, are playing a crucial role in the rebuilding process. Latino immigrants have also been instrumental in volunteer efforts. During the fires, many Latino immigrants gathered hoses and buckets to help extinguish flames in their neighborhoods, showing their commitment to their communities.

However, many Latino workers are already facing significant challenges, including job loss, health hazards from cleanup efforts, and the looming threat of immigration enforcement. While not all workers in the recovery effort are undocumented, immigration-related fears are affecting entire communities, influencing workforce participation and access to resources.

For many immigrant workers, the risk of deportation has made it difficult to seek new job opportunities in fire recovery efforts. Organizations like the National Domestic Workers Alliance and IDEPSCA (Instituto de Educación Popular del Sur de California) have mobilized to provide relief funds and resources for affected workers, yet many are hesitant to access public services due to fear of enforcement actions. Nancy Zuniga, director of worker health at IDEPSCA shared with the LA Times that the number of people going to IDEPSCA’s day laborer centers has dropped since President Trump took office for his second term.

The reconstruction effort in Los Angeles relies heavily on Latino workers. According to the UCLA Latino Policy & Politics Institute, Latinos make up 34% of the workforce in the Palisades fire zone, including the Pacific Palisades, Topanga, and Malibu areas, while representing only 7% of the area’s population. Latinos also make up 35% of the workforce in the Eaton fire zone, and 47% in the Hurst fire zone. Many of these workers face systemic inequities, including low wages, lack of health protections, and unstable employment conditions. The fires have only worsened these vulnerabilities, with many losing jobs in the aftermath of the disaster.

Silvia González, Director of Research at the UCLA Latino Policy & Politics Institute, emphasized that recovery efforts will take years and must include long-term plans to support the workers on the frontlines of reconstruction. “This is going to be a five-, six-, seven-year recovery effort,” González told LA Times. “And it’s imperative that organizations don’t forget workers so they continue to have access to resources after the cameras are away.”

Health and Safety Concerns for Workers

The California Occupational Safety & Health Administration (Cal/OSHA) has highlighted the dangers that construction workers and laborers face during post-fire cleanup. Many of the burned structures contain toxic materials, including asbestos, lead, and hazardous chemicals. Without proper protective equipment, workers are at risk of respiratory issues and long-term health complications.

State officials have pledged to conduct outreach on workplace safety, but concerns remain over whether workers—particularly those who are undocumented—will have access to necessary protections. Historically, immigrant workers have faced challenges in securing safety measures, and many fear that raising concerns could put their jobs at risk.

What Comes Next?

As Los Angeles moves forward with its recovery plan, the well-being of the workers rebuilding the city runs the risk of being deprioritized alongside broader reconstruction efforts.

Advocates argue that the city must ensure fair labor practices and protections, particularly given that construction workers will be exposed to hazardous materials for months or even years to come. Per existing labor laws, employers have a responsibility to pay wages required by law and provide necessary safety equipment. Therefore it’s up to enforcement authorities to ensure employers aren’t violating labor and safety laws.. The coming months will show whether Los Angeles and surrounding areas treat fellow Latino Angelenos and Californians fairly and with their health, safety, and families in mind.