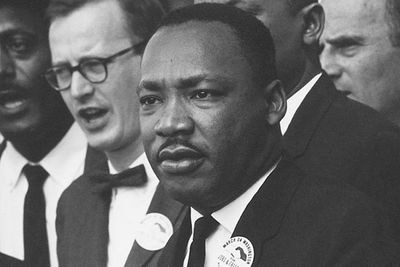

Martin Luther King Jr’s legacy in the Civil Rights space is an ever-present inspiration to all oppressed and marginalized people. MLK played a massively pivotal role in inspiring the Black community, but through his speeches, fights, and political views, he also effectively highlighted that the spirit of mutuality is where we needed to collectively focus. As MLK noted in his "Letter from Birmingham Jail," written on April 16, 1963:

“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

It’s in this spirit that he was able to influence Latino leaders and communities to join in the fight for civil rights and collective liberation.

MLK Supported Civil Right Latino Activists

MLK recognized the interconnectedness of civil rights struggles across racial lines. His philosophy of solidarity laid the groundwork for collaboration between Black and Latino civil rights movements. One of the most significant examples of this solidarity was MLK's support for César Chávez and the farmworkers' movement. In 1966, MLK sent a powerful telegram to Chávez after he marched 300 miles to raise awareness about the mistreatment of farmworkers. His message read:

"As brothers in the fight for equality, I extend the hand of fellowship and good will and wish continuing success to you and your members. The fight for equality must be fought on many fronts—in the urban slums, in the sweat shops of the factories and fields. Our separate struggles are really one—a struggle for freedom, for dignity and for humanity."

Chávez admired MLK’s work, and MLK was impressed by what Chávez was achieving for the movement. Inspired by MLK's work, Chávez and Dolores Huerta, co-founders of the National Farm Workers Association (which later became the United Farm Workers of America), launched their own marches in California and adopted nonviolent strategies like boycotts and picketing.

MLK Inspired Nonviolent Resistance in Latino Civil Right Leaders

Chávez and Huerta weren't the only Latino civil rights leaders inspired by MLK's philosophy of nonviolent resistance. Reies López Tijerina was a Mexican American activist who fought for land rights in New Mexico. He attended a gathering of Latino and Black leaders in Atlanta with MLK to plan civil rights actions. Though MLK initially had limited knowledge about Latino issues, this meeting helped bridge the gap between African American and Latino civil rights movements.

Raul Yzaguirre, former president of the National Council of La Raza (now UnidosUS), was deeply moved by King's "I Have a Dream" speech. It inspired him to expand his civil rights advocacy beyond Latino causes to include a broader vision of justice for all minorities. In a 2003 NPR interview, Yzaguirre stated:

"Although the focus was on the African-American community at the time, I think his thoughts, his sense of justice resonated with those of us who had perhaps a broader sense of inclusion, who wanted Latinos and Native Americans and other minorities to be an integral part of a civil rights movement."

MLK Wanted Latinos Involved in the Poor People’s Campaign

Gilberto Gerena Valentín, then president of the Puerto Rican Day Parade, was personally recruited by MLK to mobilize Latino participation in the March on Washington. King asked him to organize Latinos from several northeastern states to join the historic event, making the Latino community an active part of that historic moment.

It's been reported that in an interview with El Diario NY, Gerena recounted:

“Martin Luther King Jr. invited me to Atlanta, Georgia to discuss the march that was being organized, and I went there with a strong team. He personally invited me to organize the Latinos in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, and so I did.”

MLK Was Directly Engaged with the Latino Community

MLK's influence extended beyond his interactions with Latino leaders. He traveled to Puerto Rico three times, speaking at universities and addressing issues of criminality that stigmatized communities of color. In 1962, he spoke at the Interamerican University in San Germán and the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras. In 1965, he returned to Puerto Rico after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize to speak at the World Convention of Churches of Christ. During these visits, MLK addressed issues of criminality that stigmatized communities of color.

In Los Angeles, MLK spoke at the Freedom Rally in 1963 to over 40,000 people at Wrigley Field. At that rally, he sponsored special guest speaker Juan Cornejo (the first Mexican American elected to the all-white city council in Crystal City, Texas), and his presence inspired people to donate to various causes that fought for the needs of people of color. The Freedom Rally was part of MLK's broad strategy to build a coalition across racial lines because he recognized the shared struggles of African Americans, Latinos, and other marginalized communities.

MLK’s Legacy is Timeless

MLK's impact on the Latino community continues to resonate to this day. His principles of nonviolence, equality, and social justice have inspired generations of Latino activists. Dolores Huerta, reflecting on MLK's legacy in a 2022 CNN interview, emphasized the ongoing relevance of his message:

"Racism is a sickness. [...] Dr. Martin Luther King warned us that racism threatened the very foundation of our democracy. Racism began with slavery, the oppression of workers, the subjugation of women and children. [...] We have no choice but to heal."

Martin Luther King's work will always be a source of inspiration to civil rights leaders and activists across the board. Even though we’re still a massively long way from the dream he envisioned, reminding ourselves that together we can work towards a better future is the best lesson we can move forward with.

Service to his legacy means being in service to ourselves while being in service to others without getting into oppression olympics. It’s not about who has it worse, but rather acknowledging the harm, trying to move forward collectively to address it, and working towards solving it for the good of all.

- Unpacking the Birthright Debate: Is Citizenship by Birth Under Threat? ›

- Books Are Inherently Political: It's Why They Are Burned and Banned ›