New Report Confirms Latinas Devastated by COVID-19

Cut hours and wages. No additional financial support. Loosely enforced safety rules, if any at all, and a lack of childcare. These are some of the things Latinas experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a recent study from The American Association of University Women (AAUA). It’s no secret that the unprecedented health crisis derailed many lives in the past year or so, but this study revealed a more in-depth look of the economic, social and health repercussions among Latinas.

AAUA interviewed more than 40 Latinas living in states with significant Latino populations, including Texas, Arizona, and California. All come from various walks of life, including child care providers and domestic housekeepers to college faculty and small business owners. The results of the bilingual study provide direct insight of what these Latinas experienced through their own words.

Angelica from Arizona shared that “COVID has greatly affected us economically. I work as a housekeeper and have lost many days of work. Some of the homeowners got COVID, and I couldn’t go back to that house for weeks until they tested negative. We have survived because my sisters gave us money so we could pay the mortgage and buy groceries.”

Latinas faced economic disparity pre-pandemic as they were reportedly paid 55 cents to every dollar a white man made the year before. However the pandemic impacted their wallets even more. Half of the women interviewed in the survey were considered frontline or essential workers with some employed as house cleaners, medical personnel, or in the service industry, which didn’t allow them the option to work from home. About a third of these Latinas lost their jobs or had their hours reduced. It also put them at risk of exposure as these jobs require them to interact with people on a daily basis. Some reported on the lack of safety at their place of employment.

Paola from California reported that the field manager at a strawberry field contracted the virus, and “continued working and interacting with workers. He never took any precautions, even after his wife died of the virus. I told him he should set the example and stay home, but he said he needed to earn money. It was very scary to work under those conditions. I wore a face mask and gloves and took extra masks to share with my co-workers.”

With Latinas most likely to live in multi-generational homes, their risk of exposure puts their household at risk for exposure. And that was the case as the study revealed that some of the women’s households were infected by COVID-19 in addition to mental health issues.

Berta’s whole family, including herself, got COVID in Arizona. “All seven of us were very sick; it is a horrible illness. We don’t have health insurance, so we used home remedies and lots of prayer to get through it. We survived with the help of friends who dropped off food.”

“In November 2020, I suffered a terrible bout of depression after another layoff at the packing house,” Paola from California said in the report. “I was an emotional wreck; I spent an entire month in bed. I was living on $225 a week from unemployment benefits, and I constantly worried we would lose our home if we couldn’t pay rent. I can’t afford health insurance, so I relied on help from a psychologist friend from Mexico.”

Paola and Berta are among the many Latinas who don’t have health insurance or access to healthcare. That access is even harder in states, such as Florida and Texas, that didn’t expand their Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act.

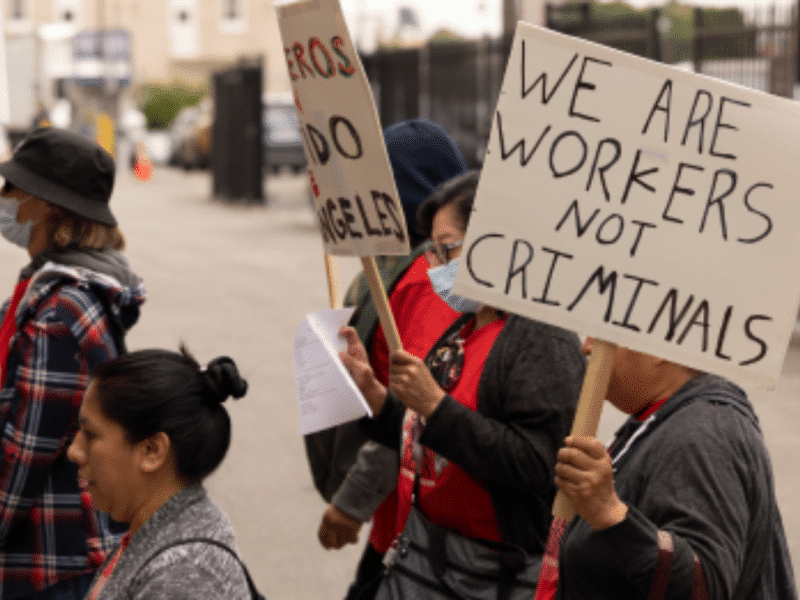

Undocumented women’s status makes that access even harder, even with financial relief. Undocumented residents and children of undocumented parents were not allowed to access beneits form the CARES Act of 2020, even if those workers, such as farmworkers, are considered esesential workers and are the reason so many Americans can purchase produce at the store. However, this year’s American Rescue Plan still excludes undocumented immigrants, but does include mixed-status families.

At the end of their report, AAUA provided recommendations to address these experiences, including economic aid that reaches communities in need, equitably distribution of the vaccines and access to affordable health care, extending all these to undocumented Latinas. To fix this in the long run, the organization recommends starting from the top with Congress and the Biden administration.

“Long-term, there is much that Congress and the executive branch can do to address underlying systemic gender, ethnic, and racial inequalities,” the report states. “This must include confronting labor market discrimination – historic inequities that contribute to poverty, and economic insecurity for Latinas and women generally.”