Generation Z is Bringing BIPOC Representation to Climate Activism

Climate activism is still, largely, a non-diverse movement. But these Gen Z activists are changing that.

We’re in a time where many are fighting to improve the current state of our society for a better future. Political affiliations, racial divides, virus health hazards–these are issues at the forefront of many minds. Youth leaders like Diana Fernandez are working to ensure we can continue to address these and other issues, housed on Earth.

“[Climate justice] is often a white-led movement—even though it should be the minorities and BIPOC folks on the frontline,” youth activist Diana Fernandez said. “They’re the ones impacted by the environment the most.”

Climate activism is growing as sustainability awareness spreads. Fracking is now a widely recognized issue, beyond first being brought to light by indigenous people. Green consumerism is on the rise and has an expensive price tag.

Greta Thunberg is a household name as a sustainability leader–but why not Mari Copeny, a youth activist who began raising awareness of the water issue in Flint, Michigan at eight-years-old? Or Autumn Peltier, a Canadian Indigenous youth named Chief Water Commissioner for the Anishinabek Nations in Ontario, Canada. Or, what about Xiye Bastida, a Mexican-Chilean climate activist who received the 2018 “Spirit of the UN” award. Environmental racism runs deep and Generation Z is working to bring BIPOC representation to the sustainability movement.

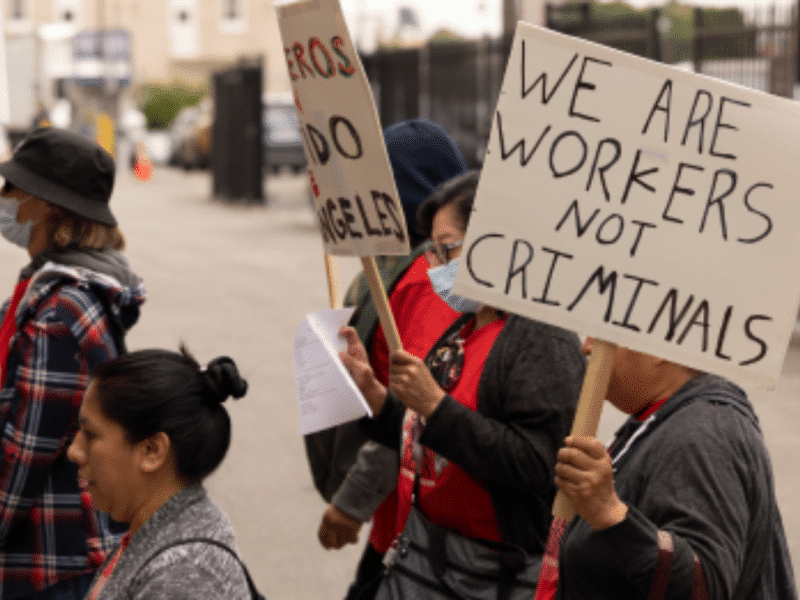

Environmental justice is a reaction to environmental racism. Zero Hour, is a youth-led climate justice organization where Fernandez works. The organization fights this form of racism through the People’s Platform, that calls for all to work together in retrofitting housing for sustainability needs to creating affordable mass transit systems to restorative work like trees on Indigenous land. Zero Hour works to diversify the voices in climate and environmental justice conversations to preserve a livable future.

Sustainability is about maintaining a balance between the economy, society, and the environment. However, it’s marketed exclusively to groups that can afford newly fabricated and/or up-cycled, environmentally-friendly products like organic foods and natural supplements.

“What can help make a difference is the inclusion of minorities and low-income communities that can’t afford those items, Fernandez said. “It’s about making a sustainable living available to the majority, not just the one percent.”

Fernandez feels sustainability is about taking action, not solely about consuming new sustainable items. She believes sustainability products shouldn’t come with a high price tag as these brands aren’t playing an appropriate role in the environmental movement.

“I can’t afford an electric car or these cute zero waste things that you have in your house,” vegan educator Destiny DeJesus said. “But [how BIPOC contribute to sustainability], is we turn lights off when we leave the house. We’re the ones taking public transportation. We’re saving plastic bags and reusing them.”

DeJesus is a coordinator with Veggie Mijas, a collective where the BIPOC community can gather, discuss, and learn about a plant-based lifestyle. It’s common for many to choose a plant-based diet due to the environmental impact of the meat industry. But DeJesus made this adjustment to live a healthier life. Growing up in a Puerto Rican household in New York, eating empanadas and pasteles she learned how to alter these meat-based dishes for her vegan diet. Replacing beef with mushrooms in her empanadas has been difficult for her elder relatives to understand.

“It’s hard to tell someone who has lived 60 or 70 years, ‘now we’re eating plants,’” DeJesus said. “They’re not very receptive to that because they think, ‘oh you need the Puerto Rican chicken soup.’”

DeJesus claims she can “veganize anything.” She’s been able to convince her Nana to eat vegan staples like quinoa, but veganism doesn’t interest half her family. Her vegan journey started after moving to Texas. Attending vegan events, she realized she was one of a few persons of color in attendance. So, she started the Veggie Mijas Dallas Chapter.

“Veganism, in general, is very white-washed,” says DeJesus. “When you [search online] ‘vegan,’ you’re going to see a bunch of pictures of white athletes and yoga people. Because the face of veganism is so white, I was like ‘we need to create our own space for vegans of color because we experience different things.’”

Fernandez’s family understands her climate activism as wanting to preserve their home. Through her work of fighting climate injustice, specifically in their community, her parents view this as a way of protecting the Latinx community. Fernandez’s parents grew up in Cuba in the ’90s, where she said the impacts of climate change weren’t the first things on their minds.

“There’s much more of a conversation about climate [in the United States],” Fernandez said. “But, there is a lack of understanding about sustainability and the climate movement because of language barriers.”

Many minority and low-income communities aren’t involved in the climate movement. Limited income makes it difficult to afford pricier green products like organic food. Minority communities often face a language barrier to receiving information and resources. Many climate organizations are failing to provide resources in Spanish or to outreach in Latinx communities.

Although these spaces are primarily occupied by white people, it doesn’t mean sustainable BIPOC leaders or businesses don’t exist. Fernandez mentions she was attracted to This is Zero Hour because their diverse representation includes Latinas.

DeJesus says there are a handful of Latina eco-businesses in the Dallas area, while her social media feed is full of young Latina climate activists.

“We’re doing the work, we’re just not getting any credit for it,” says DeJesus. “We’re not the ones driving electric cars and living in fancy Pinterest looking eco-friendly houses that we can post on social media. We’re doing the hard, dirty work in our communities, but no one is seeing it.”

The “work” is by already living a sustainable lifestyle to save money. DeJesus mentions BIPOC communities perform daily acts of sustainability like not running the A/C when out or running the water for too long. She acknowledges that it’s a privilege to not be sustainable.

“Those little things are super important,” DeJesus said. “We don’t have the agenda of saving the environment because we’re just trying to survive…we’re doing it for economical reasons as opposed to environmental reasons and because of that we’re not being highlighted.”