Women’s History Month and the Disproportionate Centering of White Women

Women’s History Month is meant to celebrate the achievements, resilience, and contributions of women across all backgrounds. But does it?

Women’s History Month is meant to celebrate the achievements, resilience, and contributions of women across different backgrounds. But every March, the historical retellings and the images that support them often depict what appears to be largely white Women’s History Month. The narrative disproportionately centers white women’s stories, struggles, and victories, and engages in the erasure or minimizing of the experiences and contributions of women of color, queer women, disabled women, and others whose identities don’t fit neatly into the mainstream white feminist mold.

The persistent exclusion of these voices is a glaring symptom of white feminism—the version of feminism that prioritizes white women’s experiences and assumes that progress for them means progress for all.

White Feminism and Its Impact

White feminism operates under the assumption that gender inequality is the primary issue facing all women, ignoring the intersecting oppressions of race, class, and other identities. Historically, this has been evident in major feminist movements. The suffragette movement, for example, was largely led by and for white women, with little concern for the fact that women of color, particularly Black women, were still barred from voting long after the 19th Amendment was ratified. More tellingly, the contributions of Black women to the suffragette movement were often excluded from mainstream narratives.

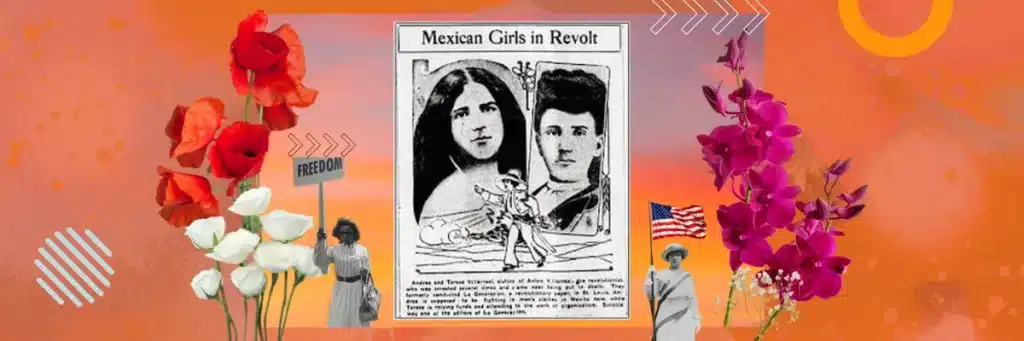

Sojourner Truth, known for her powerful speech “Ain’t I a Woman?”, highlighted the intersectional oppression faced by Black women, challenging both gender and racial biases. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper emphasized the need for racial equality alongside gender equality, pointing out the white suffragists’ failure to prioritize racial justice. Ida B. Wells, a journalist and anti-lynching activist, founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago and participated in the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., despite facing segregation attempts. Even so, Black women were frequently excluded from leadership roles and organizing committees within the movement. The 1913 suffrage parade, led by Alice Paul, exemplified this exclusion, as Black women were initially asked to march at the back of the procession.

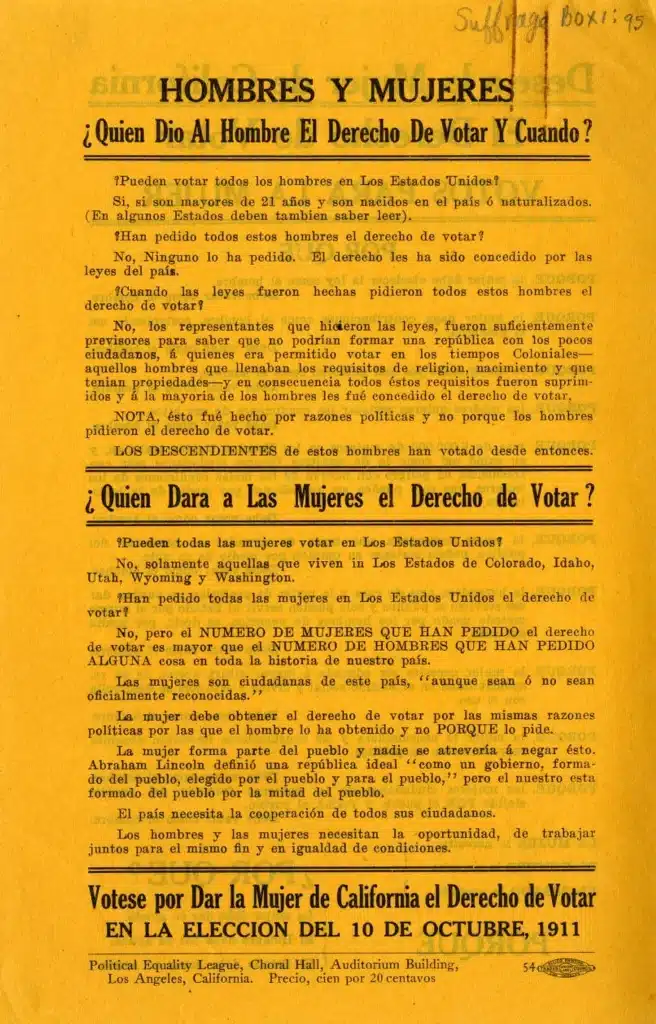

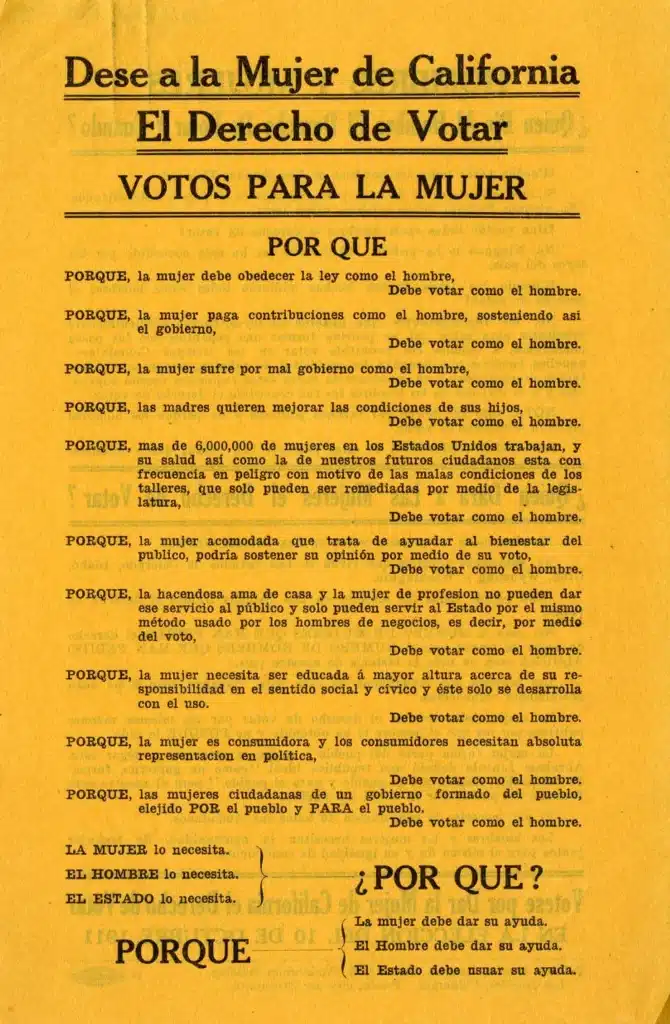

Contributions made by Latinas have also been excluded from mainstream narratives. For instance, Mexican American Maria Guadalupe Evangelina de Lopez was a key figure in California’s suffrage movement. She worked to bridge the language barrier by translating speeches and pamphlets into Spanish, allowing Hispanic women to engage in the movement. Her efforts were instrumental in the passage of California Proposition 4 in 1911, granting women the right to vote in the state.

Adelina Otero-Warren was a leader in New Mexico’s suffrage movement and she pushed for suffrage literature to be published in both English and Spanish, ensuring broader accessibility. As the first female superintendent of Santa Fe schools, she played a vital role in securing the ratification of the 19th Amendment in New Mexico and continued advocating for women’s rights, education, and child welfare.

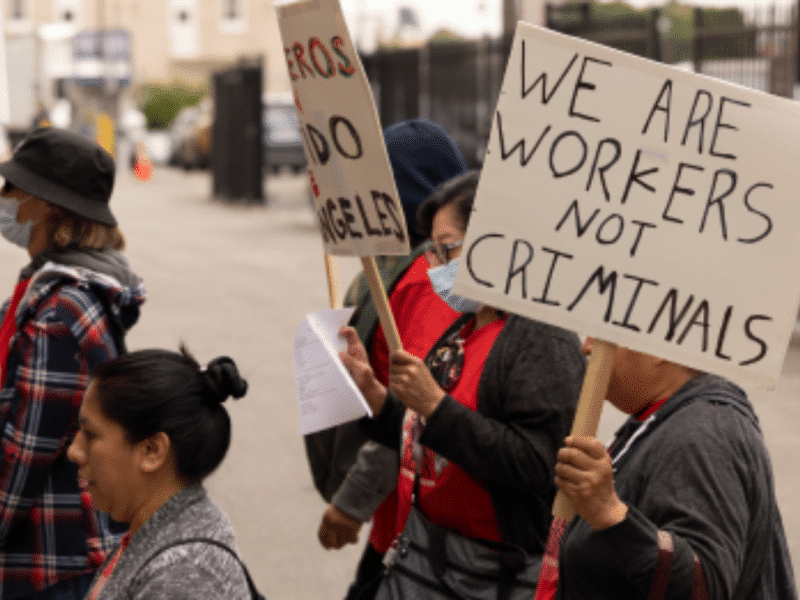

Even in modern activism, white feminism continues to dominate. The #MeToo movement is a prime example—originally founded by Tarana Burke, a Black woman, in 2006, the movement only gained widespread attention when white Hollywood actresses began to speak out in 2017. The message was clear: white women’s voices are amplified, while the contributions of women of color are often sidelined, if not erased entirely.

Women’s History Month and the Illusion of Intersectionality

Intersectionality—a term coined by legal scholar and civil rights advocate Kimberlé Crenshaw, a Black woman—acknowledges that women of color experience gender inequality differently due to their race, class, and other social factors. But despite the term’s mainstream adoption, many feminist spaces treat intersectionality as a theoretical concept rather than an actionable framework. Too often, it’s used as a buzzword to suggest inclusivity without any real effort to center marginalized voices.

Many women of color report feeling dismissed in feminist circles, their concerns deemed “too niche” to be prioritized. Discussions about pay inequality, for example, often focus on the gender pay gap between white women and white men, ignoring the even wider gap for Latina, Black, and Indigenous women. This exclusion reinforces a hierarchy where white women’s struggles are treated as universal, while the struggles of other women are seen as secondary.

The Data Doesn’t Lie

Research has shown that feminist organizations often take an additive approach to intersectionality—simply including a few women of color without fundamentally changing their structures. A study examining equality organizations in England and Scotland found that this approach actually maintains white supremacy rather than challenge it.

In the U.S., women of color are still underrepresented in leadership roles within mainstream feminist organizations, despite their significant contributions to activism and advocacy. According to a Candid report, Black and Latino CEOs/EDs are significantly underrepresented at the executive level in nonprofits, making up only 15% and 6% of CEOs/EDs, respectively. They are more likely to lead smaller organizations than larger ones.

The mainstreaming of intersectionality has also failed to shift the focus away from white women’s experiences. Instead, it has often been used as a means of performative allyship, where organizations claim to be inclusive while continuing to uphold the same exclusionary structures.

Women’s History Month Should Be for All Women

Women’s History Month has the potential to be a celebration of all women, but as long as white feminism continues to dictate the narrative, it will remain incomplete. A more equitable feminist movement would actively center the voices of Black, Indigenous, Latina, Asian, and other women of color—not as an afterthought, but as essential to the fight for gender justice.