Shaping Hollywood to Be More Inclusive of Latinas, One Story at a Time

I know it’s been a while since any of us have left our homes to hit a movie theater, but ask yourself, what was the last big-budget movie you saw that even featured or included a Latina?

When was the last time you saw a Latina on the silver screen?

I know it’s been a while since any of us have left our homes to hit a movie theater, but ask yourself, what was the last big-budget movie you saw that even featured or included a Latina? The two examples that come to my mind are Knives Out and Hustlers. A dedicated nurse and friend to a recently murdered patriarch, and a stripper who starts a lucrative operation scamming Wall Street clients.

Both roles embody a lot of stereotypes about Latinas. Ana de Armas is an immigrant. Her mother is undocumented. She’s at the mercy of that rich family. She’s a pawn, a conservative talking point, an example of the “good kind of Latina.” J.Lo is amazing in the role, her pole dance moves are fantastic, but she’s perpetuating the oversexed Latina trope.

Those two characters were pivotal to those films, and that’s huge progress. Not too long ago, Latinas only played minor supporting characters. But there’s more work to be done. This Spring I had the pleasure of teaching a new course at UCLA Extension called “Inclusive Screenwriting.” It’s a course designed to talk about race, representation and crafting inclusive stories for broad audiences. It’s one of the ways where I’m actively fighting to get more people who look like me to be represented in the mainstream media.

Even in my classes that are not about inclusion, I bring examples from a variety of films. In part, because I want everyone to feel represented, but also because I don’t want any of my students who are still finding their voices as writers to feel like there’s no room for their stories.

We need to create that space in the industry for a variety of stories. The only way to do that is to write screenplays that are unique and inclusive. One of the biggest things keeping some of these doors completely shut to underrepresented writers is the old mentality that talent finds a way.

If you are brilliant, if you are good enough, it doesn’t matter who you are, you’ll get there. If someone from a marginalized group has not had their break in the industry, their moment in the sun, that means they just aren’t that talented. This mentality helps a lot of gatekeepers sleep at night without having to take a long hard look at which voices they chose to support and which they chose to keep out of the industry altogether.

This is a sentiment I’ve heard people in positions of power echo throughout the industry for a while. Just be brilliant and you’ll get hired. There’s no systemic discrimination happening here. I have personally met brilliant writers who never had their break.

Even though the numbers don’t lie, movies with a diverse cast make more money than the ones with all-white casts, there’s still resistance to get those films greenlit.

Pointing out this imbalance, talking about race, discrimination and the lack of representation gets really uncomfortable for everyone involved. Usually, white people are overcome with a mix of shame and guilt. Sometimes they get defensive. It’s not their fault they were born in a position of privilege.

As a Latina, I’m not immune to the guilt. There are other groups who have faced far more than my group has. All we have to do is look at our past, you know, late May, early June of this year, when the country and subsequently the world, erupted in protests and solidarity for the Black community and the Black Lives Matter movement. We know there’s always someone in a worse position.

My teaching experience this past quarter was particularly unique. The COVID-19 pandemic and the stay at home orders forced all courses to be held online. This was a new experience for me and I wasn’t sure I was ready for it. None of us were. We were all tense, tired, anxious, and at home full time, trying to juggle family and work. My students showed up raw for the classes.

Still, what made class possible was the space we created to talk about race. Because that was the main idea behind this course, it was okay to come in and talk about race. Not just okay, it was part of the curriculum. We all shared personal experiences, good and bad. I talked about the times I felt I made a difference just by being hired on a project. How my female point of view was heard and addressed, how I created change, even if small, just by being involved with a film and speaking up. I also shared some negative experiences. I showed up ready to be vulnerable with them.

Each of my students brought amazing stories to the class. In every one of those stories, a different aspect of the human experience was explored. All of those stories had an underrepresented character at the center of the story.

I’ve made a habit of asking my students what their biggest takeaways from the class are. Let me share what my biggest takeaway from teaching this course for the first time was: underrepresented communities are reclaiming their stories. They are rejecting the negative stereotypes, the role of token characters, and they are refusing to stay in a supporting role by creating raw and authentic stories.

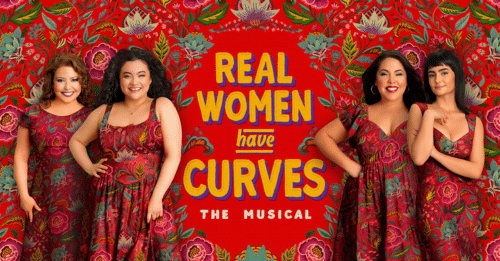

So, hopefully, the next time you see a Latina in a film, she won’t be one dimensional, hot-headed, oversexed, a servant, or simply the objective of someone’s desire. She will be a fully developed character with an arc, a full human being, with hopes, fears and flaws, just like we are in real life.

Julia Camara is a Brazilian writer/filmmaker. Born and raised in São Paulo, Brazil, she freelanced for years as a Portuguese translator for film and television subtitling. She has written and directed several award-winning short films, and teaches Screenwriting at UCLA Extension Writers’ Program. She can be found on her Instagram @julia.camara.writer