In The Community

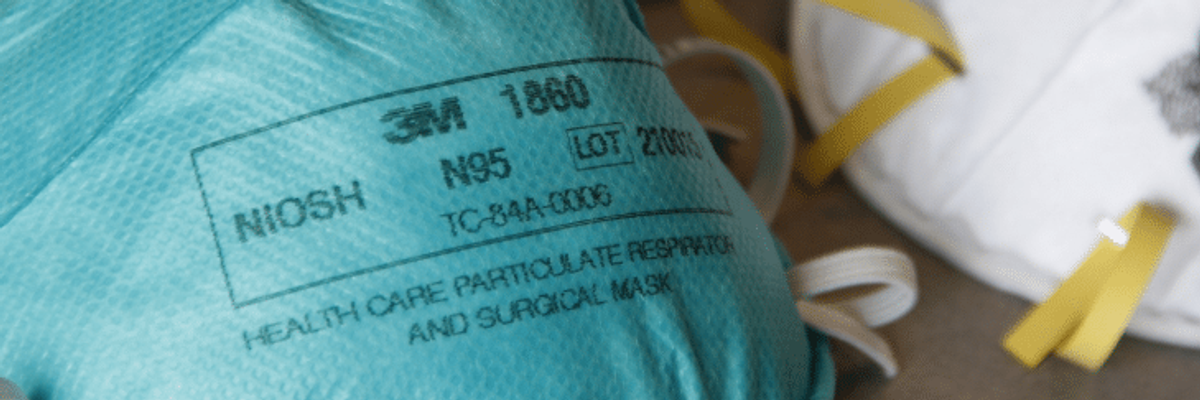

Last week, the Biden administration announced that to help continue to slow the spread of COVID-19, 400 million NIOSH-approved N95 masks would be shipped out from a government stockpile to pharmacies across the country. According to the Wall Street Journal, masks are now available at almost all locations that have also been part of the government’s vaccine distribution program.

Availability of the free masks also includes community health centers, which have been an effective way of delivering healthcare to underserved communities that have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. The CDC now reports that high-quality N95 or KN95 masks are more effective than cloth masks at protecting against the various COVID-19 variants. For a complete list of participating health centers, visit the HRSA website.

CVS, as well as several national pharmacies, expect to be stocked the first week of February and will continue “on a rolling basis as additional supply becomes available,” a CVS spokesperson said. Rite Aid and Walgreens already have masks available at select locations. Participating pharmacies have signs designating them as a mask distribution location, and all have information on their participating locations on their websites. No insurance or identification is needed for the free masks, but there is a limit of 3 masks per person, which means every household member can get up to 3 masks each.

The pandemic rocked our worlds in many different ways. One of the most consequential of those ways was what jobs were deemed essential, thus forcing millions to keep working as if the world wasn’t experiencing an unprecedented global event. Doctors, nurses, CNAs, paramedics, and other healthcare workers rightfully earned heaps of praise for their heroic work, but what about those who are overlooked, also struggled, and deserved the same amount of praise for doing their essential work as well? These 5 most thankless but most valuable jobs are just as deserving of praise. It's clear our society can't function without them.

Housekeepers and General Cleaning Staff

They wipe, sweep, and dust all corners of their employers’ homes, offices, and hospitals. This work became even more challenging as they were constantly exposed to environments infected with COVID-19, and were over-impacted by the deadly virus. The profession is over-represented with Latinas, and they also suffered from work instability when everything closed down, with many business and home employers choosing to stop paying their home cleaning staff.

Cleaning includes everything from making beds to wiping bodily fluids off surfaces. It can’t be easy to clean up areas where communicable diseases are found, but cleaning staff do the work that so many simply won’t. They often do it selflessly for the benefit of our communities, often out of economic necessity, and oftentimes for both reasons. Be kind to cleaning staff next time you interact with them. They deserve it.

Childcare Workers

This one's a biggie. Childcare workers step in and ensure the safety and well-being of America's children while their parents are out exchanging their labor for money. During the pandemic many childcare workers and pre-school teachers faced big decisions to stay at their jobs or not. Their services were also deemed essential when other essential workers needed their children taken care of. But going to work at a place where the risk of transmission was very high because of how easily germs spread amongst children was a challenge that they all took on as the heroes that they are.

Elisabeth Tobia; a CEO at two early learning centers in Michigan, highlighted the struggles of childcare workers, pointing out how despite being so important for the functioning of our society, they are some of the lowest-paid workers in the U.S, many making only little more than fast-food workers. If you value your children, you should value the people who take care of them.

Farm Workers

One of the backbones of our society. They’ve maintained food readily available for us to consume by working every single day where they were constantly exposed to COVID-19 and other horrific work conditions. As reported by Rosa Tuiran and Nick Roberts, agricultural worker Osmar Orellana shared how afraid he felt having to go to work every day but how he did so regardless.

They further reported that farmworkers were amongst those with the highest risk of contracting COVID-19 due to the conditions in which they work, where social distancing was impossible and supplies, such as water and toilets are shared amongst many.

Despite all of this, they never stopped working and suffered the brunt of the worst of this pandemic while Americans found food on their store shelves without interruption. The MVP award goes to the people who are the reason America has food on their plates, no matter what environmental catastrophe is happening.

Food Workers

While most restaurants shut down during the pandemic, many were deemed essential, including fast food establishments that remained open throughout the health crisis. They are some of the most undervalued workers and are often mistreated by customers.

A casual poke around social media will easily lead you to viral videos of food workers being yelled at, mistreated, or assaulted, and the mistreatment became even more common the further the pandemic progressed. Limited amounts of people were allowed into establishments at a time which meant they had to work twice as hard and twice as fast to get through the long lines that formed outside. Reporting on how difficult it’s been for these workers is common, with most of the reporting describing the mistreatment they endured and the difficulty they faced in navigating the pandemic. As with all service workers, be kind when ordering your next meal.

Caregivers and Home Healthcare Workers

Caregivers ensure that the most vulnerable are taken care of, at all times. Many of the people they take care of were at the highest risk of contracting COVID-19, turning their already difficult job into more of a struggle. They aren’t even remotely close to getting the recognition they deserve and yet, the demand for their services has increased significantly since the beginning of the pandemic. Caregivers and home healthcare workers were oftentimes the only people that the most vulnerable had any access to; otherwise, they would be without a single soul and unable to care for themselves.

It’s no secret that such a commitment can challenge their emotional well-being. UNICEF put together a guide, “Caring for Caregivers during the Covid-19 Crisis,” which was not only an amazing resource but also a great reminder of everything they do for us and how we have to look out for them as well. Thank them and recognize their hard work next time you see one.

“I’ll call the migra on your parents,” Mariela Camacho remembered hearing from her schoolmates growing up in San Antonio, Texas. “Kids would say that to be mean,” said Camacho, the daughter of Mexican immigrants. “I don’t think they knew what they were saying, but it was a threat.” Those words left a lasting impression. And it’s one reason why Camacho raises funds for immigrant and other marginalized communities through her business, Comadre Panadería, even during a global pandemic.

Camacho started Comadre Panadería in 2017 while living in Seattle. She associates “comadre,” with her mom who would use it with Camacho’s aunts. “Comadre is your homegirl, a friend who looks out for you,” Camacho writes on her website. She always knew she wanted to work with food even though she didn’t have the best relationship with it growing up. Her parents worked multiple jobs, so she lived off fast food like Taco Bell and Little Caesars. She still remembers the taste of the packs of chocolate chip cookies her dad brought home from his job at the Hilton Hotel. “My mom was a really good cook,” Camacho said in a recent phone interview with Luz Collective. “It’s just that they both worked so much.”

She worked in her first kitchen when she was a teenager in San Antonio and eventually moved to Austin. When she wanted a change from Texas, she moved to Seattle in 2014, where she honed her skills and learned about sourcing local and more ethically sourced ingredients. But eventually she found herself missing Texas, along with her family and the food, particularly pan dulce and breakfast tacos. “I miss everything that I grew up eating and was a part of my life every single day,” said Camacho.

She was also tired of hearing that she had to work in a French bakery to gain legitimacy. “It was the standard to make French pastries,” said Camacho. “All the bakeries were French. That’s what you compared your work to. That’s the books you bought. Those were the chefs you inspired to be.” But to her, making the pastries she grew up eating required just as much skill and training. “Why are we not giving pan dulce and these Latin American baked goods the same respect?” said Camacho. “I want people to respect the food I grew up eating.”

So Camacho started making pan dulce with organic ingredients to sell at pop-ups around Seattle. On the menu are empanadas (pies with sweet or savory fillings), pink cake (corn cake with pink frosting), traditional conchas (brioche bread topped with a cookie shell resembling a seashell) and some vegan and gluten-free options.

Seattle is a predominantly white city with people of color making up 35 percent of the population (Latinos make up just 6 percent). But when Camacho started offering these traditional pastries, her business started to pick up with wholesale and personal orders outside the pop-ups. “I was surprised, but it was really amazing just how people wanted to eat the food that I was making,” said Camacho.

The chef had to shift her business model once the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in March, two months after she moved back to San Antonio. She left Seattle with the intention to break away from her 70-hour workweek and travel with her bakery, but her 13-year-old dog Stevie had a health issue that used most of Camacho’s savings (Stevie is now fine). Before COVID-19, she was looking for a retail space, but quickly changed plans. “I just didn’t feel comfortable doing that anymore because I didn’t know what the next couple of months were going to look like,” said Camacho.

Many businesses, including small businesses like Camacho’s, shuttered their doors to decrease the risk of spreading the virus, which also left employees out of work. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported last week that unemployment rose to 14.7 percent, representing 20.5 million people who have lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic. For Latinos, the rate is 18.9 percent, the highest for any racial group. That means nearly 1 in 5 Latinos are unemployed.

Add that reality to the fact that up to 90 percent of minorities and women owned businesses didn’t receive Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans because they didn’t qualify or the funds were depleted by the time they applied. Camacho is self-employed and didn’t apply for a PPP loan, but she did apply for an Economic Injury Disaster Loan. She requested $10,000 but only received $1,000, which she said was still helpful to her. “Really anything is helpful at this point,” said Camacho. “I always knew that the government wasn’t really going to help me through this time anyways, so for me, it feels like keep trying to do your own thing and work your way through it. There’s so many other people that need more help than you, so you just keep on chugging away.”

And that’s what she did. She has shifted her business from pop-ups to weekend deliveries in San Antonio and Austin, cities that are an hour and a half apart, with her partner’s help. She’s also continued to use her business to fundraise. Most recently, she donated a portion of her Mother’s Day sales to Sueños Sin Fronteras de Tejas (SSFTX) Empowerment Fund, a San Antonio-based collective led by Latinx and Women of Color that provides “health and healing support and access to immigrant womxn and children in the U.S.” Camacho was introduced to them when she returned to San Antonio and did a similar fundraiser for them earlier this year. “I think they’re doing really amazing work,” said Camacho. “I love the work that they’re trying to do specifically with women or women-identifying people, so I felt that I really wanted to raise money for them for Mother’s Day.”

Her inclination to help others stems from growing up with immigrants and watching them get taken advantage of at work. She just wants better for people. “In my mind, how can you not be furious and actively try to change things,” said Camacho. “That’s also me coming from my privilege. I totally understand that not everyone can do something or be proactive about stuff, but I am luckily able to do something. So as long as I can, I will.”

Camacho will continue with deliveries until she can figure out how to return to pop-ups and grow her business safely and responsibly. “I’m just taking it day by day, trying to do the right thing and stay afloat,” said Camacho.