In The Community

Abortion is a deeply personal decision and experience, and it’s also a topic surrounded by misconceptions. Some of the misconceptions we’ve blindly accepted throughout our lives, but it’s important to look into them and correct them. The better we understand abortion, the better we’ll be able to speak about it and understand it as a fundamental piece of reproductive rights. Here are 7 myths about abortion debunked:

Abortion causes breast cancer

Photo by Angiola Harry on Unsplash

Photo by Angiola Harry on UnsplashThe fact is there’s no scientific evidence linking abortion to an increased risk of breast cancer. The American Cancer Society, American Medical Association, the World Health Organization, Planned Parenthood, and numerous other reputable health organizations have all stated that abortion doesn’t cause breast cancer.

Most people regret their abortion

Photo by Ahtziri Lagarde on Unsplash

Photo by Ahtziri Lagarde on UnsplashThis is a very common myth and one of the most common arguments among pro-life people. However, looking at the numbers suggests otherwise. Most people don’t regret their decision to have an abortion. In 2020, a UC San Francisco study showed that over 95% of women surveyed five years after having an abortion reported that it was the right decision for them. The decision to have an abortion is deeply personal, and only the individual and their healthcare provider can determine what’s best for their health and life.

Emergency contraception and medication abortions are the same thing

Photo by Benjamin Moss on Unsplash

Photo by Benjamin Moss on UnsplashEmergency contraception and medication abortion are not the same thing. Emergency contraceptive pills, often known as the morning-after pill, are designed to prevent pregnancy after unprotected sex. Medication abortion involves taking prescribed pills to terminate an existing pregnancy. Understanding the difference between the two is essential to making informed reproductive choices.

Physical health concern is the only valid reason for an abortion

Photo by Klaus Nielsen

This myth is very reductive because there’s a great variety of valid reasons why someone might seek an abortion, not just physical health concerns. Economic hardships, relationship issues, the need to focus on other children, and personal readiness are all valid reasons for choosing to have an abortion. There’s also the case of pregnancy as a result of rape or forced incest. Everyone’s circumstances are unique and the choice of seeking an abortion is as personal as it gets. It should be respected instead of policed.

Abortion leads to fertility issues

Photo by iStrfry , Marcus on Unsplash

Photo by iStrfry , Marcus on UnsplashAbortion doesn’t affect fertility and this myth has been debunked for a long time. Abortion rarely leads to infertility issues and there’s no evidence it’s associated with infertility risks. People can conceive again shortly after having an abortion if they choose to. This myth can cause unnecessary fear and anxiety, but the science is clear: abortion does not impact long-term fertility.

Abortion causes “Post-Abortion Syndrome”

Photo by Felipe Cespedes

Post-abortion syndrome isn’t recognized as a medical condition. While individual experiences vary, most people don’t experience long-term psychological or emotional problems after an abortion. Many women report feeling relief after the procedure. It's normal to have a range of emotions, especially if the decision is difficult, but having support during and after the process can help process those emotions healthily.

Medical abortion is painful

Photo by RF._.studio

The experience of a medical abortion can involve bleeding and pelvic cramping, particularly in the first 24 hours after taking the misoprostol tablets. However, pain relief options exist to manage the symptoms. Women who are well-informed about what to expect, who have made an informed choice, and who have access to safe abortion rarely experience any issues or complications.

We hope the debunking of these myths challenges any misinformation you may have absorbed and we encourage you to share this information. Promoting factual understanding helps friends, family, and communities navigate challenging conversations about abortion with compassion and truth, and that can make a big difference.

- The Horrific Realities of the Total Abortion Ban in the Dominican Republic ›

- Texas Abortion Laws Cause Horrific Impact on Latinas: Teen Pregnancies and Assault-Related Pregnancies Surge ›

An educator with PLAN teaches young Dominican girls the basics of sexual education.

This reporting was produced with the support of the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) as part of its Reproductive Health, Rights, and Justice in the Americas Initiative.

I had never been to the Dominican Republic before, but as an ardent long-time advocate for abortion rights, I was well-versed with U.S. and global examples of the travesties women and families endure under severe reproductive rights restrictions and total abortion bans. Despite this, after a week of meeting with advocates, educators, and activists, I found I wasn’t prepared to witness the real-life devastation of a total abortion ban.

At the end of 2023, I accompanied a delegation of U.S. state lawmakers who traveled to the Dominican Republic as part of a trip organized by the State Innovation Exchange and the Women’s Equality Center. The purpose of the trip was educational and experiential. The entire purpose was to get a first-hand account of what life is like for women in the Dominican Republic and to understand what the future may hold for them in a society plagued by violent patriarchy.

This is what I learned.

The History

What is new is the community activism that’s been steadily growing to pressure politicians to, at the very least, adopt reforms known as “las tres causales” or the three causes.

After heavy and sustained national and international political and community mobilizing, Congress passed, and President Danilo Medina signed into law, penal code reforms that were set to take effect on December 19, 2014. Those reforms called for the decriminalization of abortion under certain circumstances - las tres causales. But after three religious and conservative pressure groups challenged the new law, alleging procedural errors, amongst other things, the Dominican Constitutional Court ruled that the reforms were unconstitutional.

And with that, Dominican women were once again stuck in the patriarchal culture of 1884, where science is entirely ignored and the opinion that life is guaranteed “from conception to death” reigns supreme.

The "Sanctity" of Life

The answers are grim.

The Dominican Republic has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality and adolescent pregnancies in Latin America and the Caribbean. UNICEF reports that nearly 20 out of every 1,000 babies will die within 28 days of birth, and 95 out of every 100,000 women will die during childbirth. The National Statistics Office of the Dominican Republic reports that 20% of girls and young women between the ages of 15 and 19 are mothers. The average across Latin America and the Caribbean, where abortion restrictions vary but where the majority still lean towards criminalization, is 18%.

In a society where abortion has been criminalized so deeply and where women’s lives have been deemed inferior to clumps of cells for over a century, it’s no wonder that women risk their lives to seek alternative methods of abortion or avoid seeking healthcare when they experience a normal miscarriage.

Miscarriage is very common. In fact, some research suggests that more than 30% of pregnancies end in miscarriage, and many end before a person even knows they’re pregnant.

Yet in the Dominican Republic, when a woman seeks medical assistance for a miscarriage, it’s presumed that she attempted an abortion and is immediately questioned by healthcare staff and often referred to law enforcement. The burden remains on her to prove she didn’t miscarry on purpose. And even when the viability of the fetus isn’t in danger, but the life of the mother is, healthcare professionals are so afraid of prison time that they will withhold medical treatment for the pregnant person if it means possibly inducing a medically necessary abortion.

This was the case of Rosaura Almonte, a 16-year old young woman who discovered she was 4 weeks pregnant when health complications led to the discovery of luekemia. Almonte, known as “Esperanzita” was denied treatment because the chemotherapy would put the fetus at risk of death. Both Esperanzita and her 13-week-old fetus died in 2012.

Poverty and forced childbirth are strongly correlated. The marked difference between better-resourced women and impoverished women is evident in the different levels of access to reproductive healthcare and, despite being criminalized, self-managed abortions.

In a briefing on the reality of reproductive health access that included local gynecologist and fertility specialist Dr. Lilliam Fondeur, she described how under the private health system there are privacy rights and providers who are willing to help circumvent the ban.

But under the public health care system, where no privacy rights exist for reproductive medical assistance, women like Esperanzita suffer disproportionate government-sponsored violence. Their lives are decidedly less valuable than that of a 4-week old fetus.

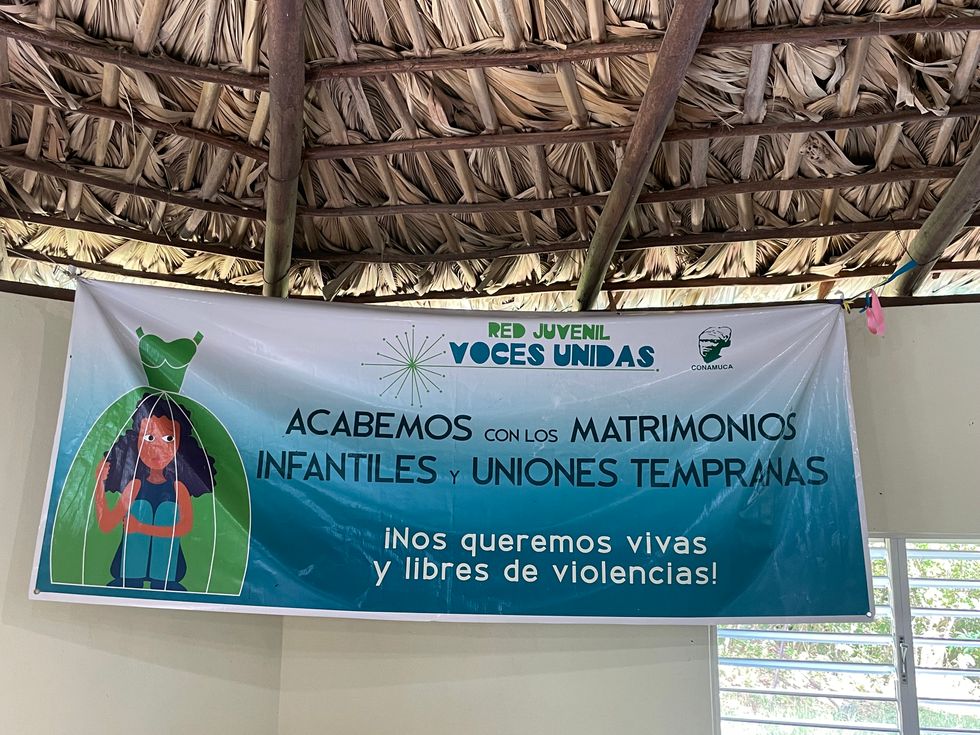

In a country where child marriage was still legal up until 2021, 31% of young women are in a legal or religious union before the age of 18, and 12% of girls are in a union before their 15th birthday. Much of the advocacy work being done throughout the country is still focused on the basic dissemination of information, letting families know that child marriage is now illegal.

It’s a daunting task to accomplish when so many barriers exist that make it socially acceptable for young girls to marry.

María Teresa Hernández with the Associated Press reports that poverty forces some Dominican mothers to marry their 14 or 15-year-old daughters to men up to 50 years older.

This cultural acceptance helps explain why nearly 7 out of 10 women suffer from gender violence such as incest, and families often remain silent regarding the sexual abuse.

The barriers for women in the Dominican Republic are steep. Dr. Fondeur shared that it’s estimated that up to 50% of Dominican Women don’t have access to birth control and that up to 30% of women are unknowingly sterilized. The forced sterilization rates highlight the hypocrisy of the “sanctity of life” argument. If god determines who gets pregnant and when, it’s curious that the government chooses to sterilize impoverished women without their consent after they have already been impregnated at least once.

The Future

While the future for Dominican women may appear grim, significant progress has been made in the last decade. Dominican activists, advocates, and educators are making inroads across society. Young women, girls, and boys are being taught medically accurate sexual education in innovative ways within and outside of the school system. Local advocates are benefiting from international support from leaders of the successful marea verde Latin-American abortion rights movement and U.S. reproductive rights leaders and elected officials.

The legislators who joined the delegation included New York assembly members Karines Reyes, Amanda Septimo, and Jessica González-Rojas; Arizona state Sen. Anna Hernandez; and North Carolina state Sen. Natalie Murdock.

Collectively, New York Assembly Members Reyes, Septimo, and González-Rojas represent the largest voting bloc of Dominican voters outside the Dominican Republic itself.

This voting bloc is so influential that in 2023 for the first time in the 41-year history of the annual National Dominican Day Parade, Dominican Republic President Luis Abinader, who is up for re-election this year, served as the parade grand marshal. He also attended the evening Dominican Day Parade Benefit Gala that same weekend in New York.

In a meeting with Dominican lawmakers, all of the lawmakers were very clear about why they where there. New York Assembly Member Septimo stated in no uncertain terms, “We’re here to support the three causes.” In an election year where U.S. influence can possibly determine the outcome of the Dominican presidential election, President Abdinar was put on notice. President Abdinar campaigned on his support of the tres causales, but has so far made no effort in moving it forward.

I must admit that seeing the abject misery that so many Dominican women are subject to in real time inspired a deep sense of despair and profound sadness. At the same time, however, I left with a sense of inspired pride and hope for the women of the Dominican Republic and the women of the United States as well, after witnessing the fire of perseverance in so many who refuse to let it be put out.

The future of Dominican women remains to be seen, but just as it’s happening in the U.S., and despite the crushing odds, there will always be an army of women who refuse to accept less than full dignity and the full freedom of self-determination that they deserve. And for this reason, the future feels hopeful despite it all.

From Puerto Rico's Trials to Over-the-Counter Access: The Evolution of the Birth Control Pill

In light of recent events where the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) greenlit the sale of Opill, a birth control pill, without the need for a prescription, the conversation about contraceptives and women's reproductive rights is once again at the forefront.

This monumental decision marks the first time consumers in the U.S. will be able to access a daily oral contraceptive over the counter without a prescription. Patrizia Cavazzoni, the director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, emphasizes that this move aims to make contraception more effective and accessible.

But as we celebrate this progress, it’s important to remember the role women of color played in the development of the contraceptive pill and other reproductive medicine advancements. From experiments on enslaved Black women to, in this case, impoverished women in Puerto Rico, the amount of women who served as sacrificial guinea pigs shouldn't be lost in the untold abyss of intentional historical erasure.

Puerto Rico, during the 1950s, was in the midst of dramatic changes. Urbanization was on the rise, and there was an aggressive push to reduce the island's high birth rate. This provided an ideal setting for American pharmaceutical companies and researchers to test their new invention—the birth control pill.

The starting point was the collaboration between Gregory Pincus, an American biologist, and Dr. John Rock, a gynecologist. Margaret Sanger, a well-known champion of birth control who also believed in white supremacist eugenics theory, was also involved in the planning. They were on a mission to create a birth control pill, but to get FDA approval, they needed large-scale human trials, and experimenting on white women was entirely unacceptable.

They looked towards Puerto Rico, mainly due to the ease of bypassing stringent testing requirements and the island's lack of regulatory protections. The U.S. had significant influence over the island, allowing for easier navigation of bureaucratic red tape. Plus, many women on the island had limited access to medical care, making them more persuadable to participate in clinical trials.

Additionally, the predominantly Catholic Puerto Rican populace had been resistant to sterilization campaigns earlier in the decade. This gave researchers a large pool of women who could potentially benefit from a non-permanent form of birth control and local non-religious leaders were on board with this.

Women in areas like Rio Piedras and Humacao were given the pill, often without full understanding or consent. They were told it was a new form of contraceptive, but the potential risks or the experimental nature of the medication were conveniently omitted.

The high hormone dosages in these early pills led to alarming side effects. Women experienced discomforting symptoms ranging from nausea and dizziness to severe consequences like blood clots and heart issues. Tragically, some even lost their lives. Yet, these repercussions were often dismissed or downplayed by the researchers. In their quest for FDA approval, the lives of these Puerto Rican women were necessary and meaningless casualties.

Deep-rooted machismo and misogyny also played its part. Women's health was secondary to the societal expectation of them as the principal agents of family planning. The trials were emblematic of this skewed perspective, putting women at risk, while the responsibility of men in family planning was sidelined.

While the trials in Puerto Rico did pave the way for the FDA's approval of the contraceptive pill in 1960, the cost at which this came remains a dark shadow. The lessons here extend beyond the importance of informed consent; they underscore the need for a holistic approach to women's health, respecting our rights, voices, and well-being.

As we embrace these new strides, with birth control pills like Opill being touted as “affordable” and “easy to obtain,” it's a stark reminder of how far we've come from the days of the Puerto Rican trials. The journey, from ethical breaches in research to a world where over 100 countries offer birth control over the counter, underscores the importance of vigilance, respect, and commitment to women's rights and health.

In our modern context, with professionals like Melissa Chen from the UC Davis Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology highlighting the convenience of such over-the-counter options, especially for those struggling to get clinic appointments, we're witnessing an era where access to contraception is becoming culturally accepted.

Yet, as we stand on the brink of this new age of contraceptive access, let's not forget the sacrifices and trials of the women of Puerto Rico. Their stories aren’t just about the past but serve as a rallying cry for the future—a future where medical ethics and women's rights go hand in hand.

- Mexican Supreme Court Legalizes Abortion Nationwide ›

- La Marea Verde: Latin-American Women's Abortion Rights Movement Gains Momentum in the U.S. ›