The Horrific Realities of the Total Abortion Ban in the Dominican Republic

In a country where abortion laws have remained unchanged since 1884, women face draconian penalties, including up to 2 years in prison for seeking an abortion, with healthcare providers risking up to 20 years.

This reporting was produced with the support of the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) as part of its Reproductive Health, Rights, and Justice in the Americas Initiative.

I had never been to the Dominican Republic before, but as an ardent long-time advocate for abortion rights, I was well-versed with U.S. and global examples of the travesties women and families endure under severe reproductive rights restrictions and total abortion bans. Despite this, after a week of meeting with advocates, educators, and activists, I found I wasn’t prepared to witness the real-life devastation of a total abortion ban.

At the end of 2023, I accompanied a delegation of U.S. state lawmakers who traveled to the Dominican Republic as part of a trip organized by the State Innovation Exchange and the Women’s Equality Center. The purpose of the trip was educational and experiential. The entire purpose was to get a first-hand account of what life is like for women in the Dominican Republic and to understand what the future may hold for them in a society plagued by violent patriarchy.

This is what I learned.

The History

What is new is the community activism that’s been steadily growing to pressure politicians to, at the very least, adopt reforms known as “las tres causales” or the three causes.

After heavy and sustained national and international political and community mobilizing, Congress passed, and President Danilo Medina signed into law, penal code reforms that were set to take effect on December 19, 2014. Those reforms called for the decriminalization of abortion under certain circumstances – las tres causales. But after three religious and conservative pressure groups challenged the new law, alleging procedural errors, amongst other things, the Dominican Constitutional Court ruled that the reforms were unconstitutional.

And with that, Dominican women were once again stuck in the patriarchal culture of 1884, where science is entirely ignored and the opinion that life is guaranteed “from conception to death” reigns supreme.

The “Sanctity” of Life

The answers are grim.

The Dominican Republic has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality and adolescent pregnancies in Latin America and the Caribbean. UNICEF reports that nearly 20 out of every 1,000 babies will die within 28 days of birth, and 95 out of every 100,000 women will die during childbirth. The National Statistics Office of the Dominican Republic reports that 20% of girls and young women between the ages of 15 and 19 are mothers. The average across Latin America and the Caribbean, where abortion restrictions vary but where the majority still lean towards criminalization, is 18%.

In a society where abortion has been criminalized so deeply and where women’s lives have been deemed inferior to clumps of cells for over a century, it’s no wonder that women risk their lives to seek alternative methods of abortion or avoid seeking healthcare when they experience a normal miscarriage.

Miscarriage is very common. In fact, some research suggests that more than 30% of pregnancies end in miscarriage, and many end before a person even knows they’re pregnant.

Yet in the Dominican Republic, when a woman seeks medical assistance for a miscarriage, it’s presumed that she attempted an abortion and is immediately questioned by healthcare staff and often referred to law enforcement. The burden remains on her to prove she didn’t miscarry on purpose. And even when the viability of the fetus isn’t in danger, but the life of the mother is, healthcare professionals are so afraid of prison time that they will withhold medical treatment for the pregnant person if it means possibly inducing a medically necessary abortion.

The Public Maternity Hospital in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic is staffed with guards and armed police. Lucy Flores

This was the case of Rosaura Almonte, a 16-year old young woman who discovered she was 4 weeks pregnant when health complications led to the discovery of luekemia. Almonte, known as “Esperanzita” was denied treatment because the chemotherapy would put the fetus at risk of death. Both Esperanzita and her 13-week-old fetus died in 2012.

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C3Bihy3OF_5/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA%3D%3D

Poverty and forced childbirth are strongly correlated. The marked difference between better-resourced women and impoverished women is evident in the different levels of access to reproductive healthcare and, despite being criminalized, self-managed abortions.

In a briefing on the reality of reproductive health access that included local gynecologist and fertility specialist Dr. Lilliam Fondeur, she described how under the private health system there are privacy rights and providers who are willing to help circumvent the ban.

https://www.instagram.com/p/C1FPdLgrtY2/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA%3D%3D

But under the public health care system, where no privacy rights exist for reproductive medical assistance, women like Esperanzita suffer disproportionate government-sponsored violence. Their lives are decidedly less valuable than that of a 4-week old fetus.

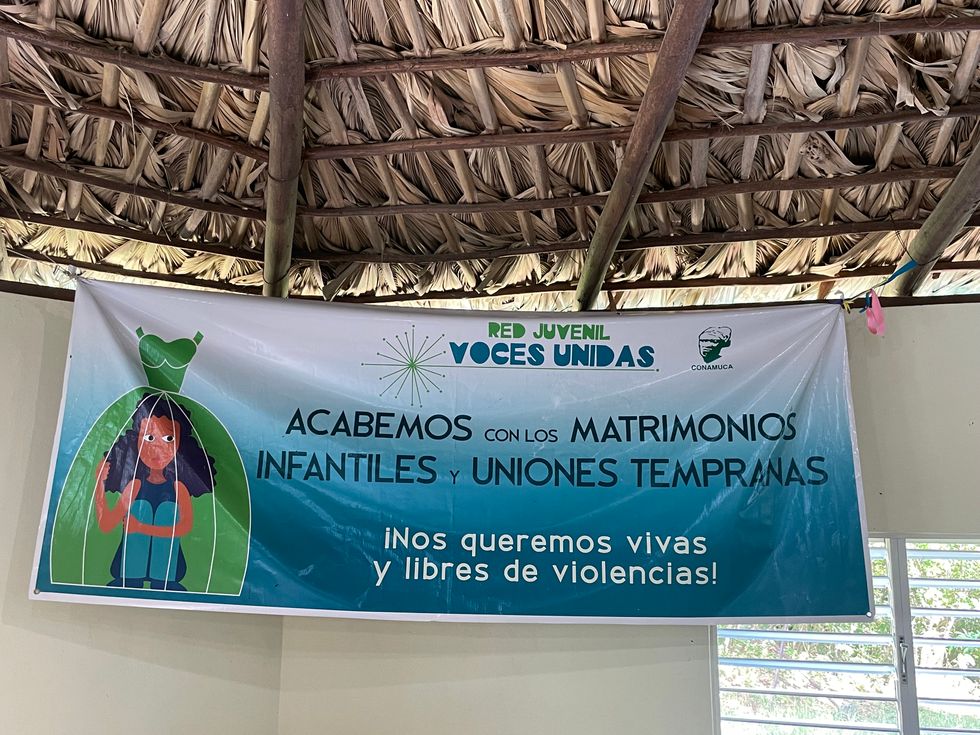

In a country where child marriage was still legal up until 2021, 31% of young women are in a legal or religious union before the age of 18, and 12% of girls are in a union before their 15th birthday. Much of the advocacy work being done throughout the country is still focused on the basic dissemination of information, letting families know that child marriage is now illegal.

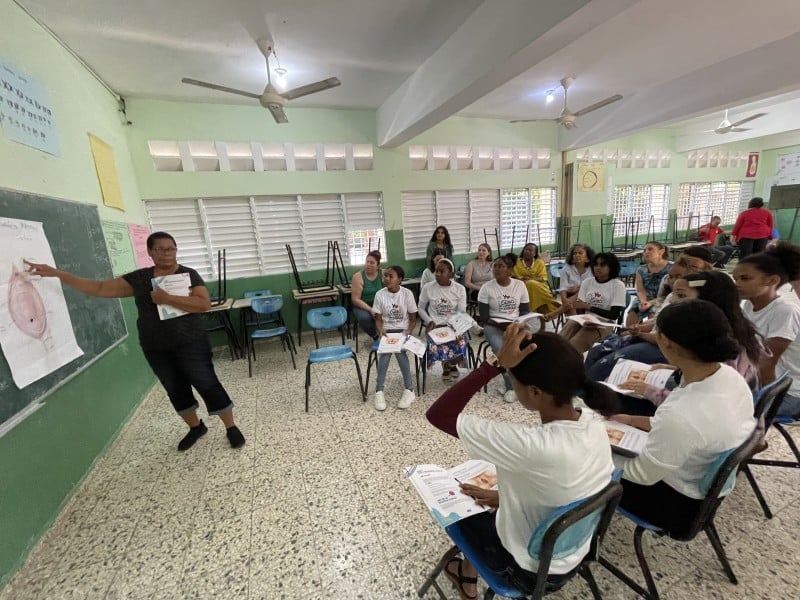

CONAMUCA, a rural advocacy organization, educates young women and families about their rights and opportunities. Lucy Flores

It’s a daunting task to accomplish when so many barriers exist that make it socially acceptable for young girls to marry.

María Teresa Hernández with the Associated Press reports that poverty forces some Dominican mothers to marry their 14 or 15-year-old daughters to men up to 50 years older.

This cultural acceptance helps explain why nearly 7 out of 10 women suffer from gender violence such as incest, and families often remain silent regarding the sexual abuse.

The barriers for women in the Dominican Republic are steep. Dr. Fondeur shared that it’s estimated that up to 50% of Dominican Women don’t have access to birth control and that up to 30% of women are unknowingly sterilized. The forced sterilization rates highlight the hypocrisy of the “sanctity of life” argument. If god determines who gets pregnant and when, it’s curious that the government chooses to sterilize impoverished women without their consent after they have already been impregnated at least once.

The Future

While the future for Dominican women may appear grim, significant progress has been made in the last decade. Dominican activists, advocates, and educators are making inroads across society. Young women, girls, and boys are being taught medically accurate sexual education in innovative ways within and outside of the school system. Local advocates are benefiting from international support from leaders of the successful marea verde Latin-American abortion rights movement and U.S. reproductive rights leaders and elected officials.

The legislators who joined the delegation included New York assembly members Karines Reyes, Amanda Septimo, and Jessica González-Rojas; Arizona state Sen. Anna Hernandez; and North Carolina state Sen. Natalie Murdock.

Collectively, New York Assembly Members Reyes, Septimo, and González-Rojas represent the largest voting bloc of Dominican voters outside the Dominican Republic itself.

This voting bloc is so influential that in 2023 for the first time in the 41-year history of the annual National Dominican Day Parade, Dominican Republic President Luis Abinader, who is up for re-election this year, served as the parade grand marshal. He also attended the evening Dominican Day Parade Benefit Gala that same weekend in New York.

In a meeting with Dominican lawmakers, all of the lawmakers were very clear about why they where there. New York Assembly Member Septimo stated in no uncertain terms, “We’re here to support the three causes.” In an election year where U.S. influence can possibly determine the outcome of the Dominican presidential election, President Abdinar was put on notice. President Abdinar campaigned on his support of the tres causales, but has so far made no effort in moving it forward.

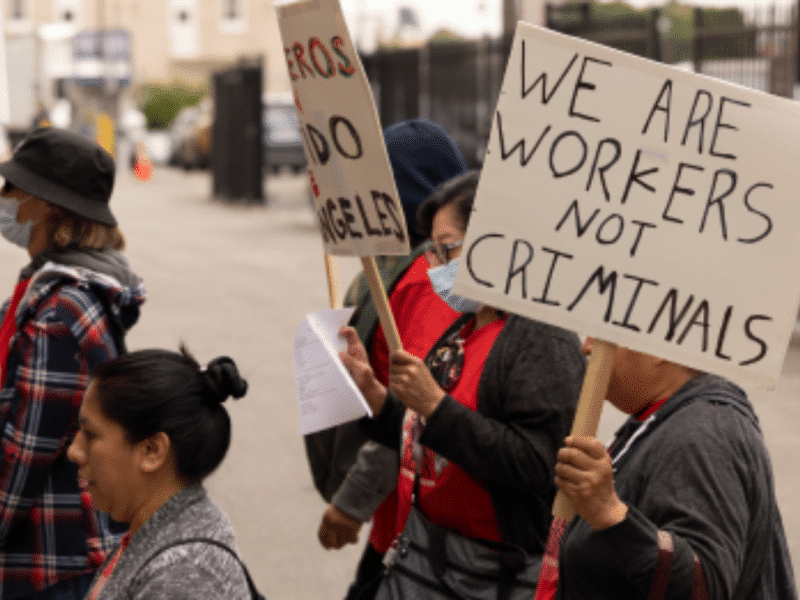

Photo by: ANA I. MARTINEZ CHAMORROANA I. MARTINEZ CHAMORRO

I must admit that seeing the abject misery that so many Dominican women are subject to in real time inspired a deep sense of despair and profound sadness. At the same time, however, I left with a sense of inspired pride and hope for the women of the Dominican Republic and the women of the United States as well, after witnessing the fire of perseverance in so many who refuse to let it be put out.

The future of Dominican women remains to be seen, but just as it’s happening in the U.S., and despite the crushing odds, there will always be an army of women who refuse to accept less than full dignity and the full freedom of self-determination that they deserve. And for this reason, the future feels hopeful despite it all.