Three Lessons the U.S. Reproductive Rights Movement Can Learn from Latin America’s Green Wave

Can women in the United States learn from the hard-fought lessons from the Marea Verde (Green Wave) reproductive rights movement? Will reproductive rights movement leaders take the opportunity to learn?

This reporting was produced with the support of the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) as part of its Reproductive Health, Rights, and Justice in the Americas Initiative.

As discussed in part one of this series, the political landscape for abortion access has taken a serious turn for the worse in the U.S. in recent years. Building off of years of legislative and legal losses (and just a few wins here and there), abortion access is now only a reality for those who can afford to travel to a state where it is legal in the U.S.

While these changes impact everyone in the U.S. who needs abortion care, Latinas in particular, are more likely to be impacted because of geography. According to the National Partnership for Women & Families, as of November 2022, “nearly 6.5 million Latinas – 42 percent of all Latinas ages 15-49 – live in the 26 states that have banned or are likely to ban abortion. They represent the largest group of women of color impacted by current or likely state bans.”

With so many people impacted by the current state of affairs, advocates are looking more closely at the strategies that have produced historic wins for abortion access in Latin American countries like Colombia, Argentina, and Mexico in recent years. Based on conversations with Latina activists across borders working on this issue, here are three lessons the reproductive rights movement in the U.S. could learn from the Green Wave.

The U.S. needs many different regional strategies

One theme that came up in a number of interviews was the fact that the U.S., while under one national government, has very distinct political and cultural environments. A better approach may be to mirror how the Green Wave has worked across countries in Latin America–share strategies but allow regions to guide their own directions.

“How is it possible that something that works in New York will work in Alabama?” asks Paula Avila Guillen, executive director of the Women’s Equality Center (WEC). “It is not even logical to think that. Something that works in El Salvador doesn’t work in Mexico doesn’t work in Colombia, doesn’t work in Argentina. There might be similarities in the strategy, but the tactical level has to be different.”

This learning comes from mistakes that were made when organizing in Latin America, says Guillen. “For many years, we tried to do the same in Latin America, treat Latin America as if we were one. Because we couldn’t make progress at the country level, we put all our efforts at the international levels. And for years, our main goal was to get legal precedents from those [international human rights] bodies. We needed to get a very big written advancement. Then our goal was to bring it back to the ground. But that assumes that everybody across Latin America will react the same to a decision that comes from an international body.”

Instead, progress came when groups within specific countries worked to tailor their strategy to the local and regional political context.

To be clear, there have always been repro groups working at the state and local levels in the U.S. But a huge percentage the resources have been directed towards the big national, mostly white-led groups who guide policy strategies and also influence messaging, in addition to directing federal strategy.

Jessica Gonzalez-Rojas, now a state assemblymember representing Queens, New York, used to run the only national organization focused on the Latina community–the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice. They are an organization that has dedicated presence and organizing in four states. “When I left Latina Institute in 2020, [our budget was] about .3 million. It paled in comparison to organizations that were white-led, that were legal serving, that were rights-based, that didn’t have a justice analysis and didn’t do as much intersectional organizing. That was the work we were doing on a shoestring budget. And it was very successful, but the scale was just not enough.”

Reclaim the moral high ground

Despite an alleged commitment to the separation of church and state in the U.S. constitution, the political debate about abortion has been subject to major influence from religious entities and a broader conversation about morality. It’s hard to argue that those in support of abortion access have won those arguments. “I feel like the opposition just really took over messaging and really claimed the moral high ground,” says Ena Suseth Valladares, director of programs for California Latinas for Reproductive Justice (CLRJ). She participated in a convening in February of this year, organized by the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice (NLIRJ,) WEC and Ipas, that brought together advocates from Latin America with advocates from the U.S.

Valladares recalls hearing from a Mexican advocate on a panel about storytelling. “They were like, we reclaim the moral high ground. For us, abortion is a moral choice, right? And in some ways, you’re violating our religious freedom by not allowing us to decide if we want to terminate a pregnancy. That’s a whole different way of talking about this issue.”

“One of the things I find fascinating and most successful about the green wave is how we forced them to change their speech,” shares Guillen. “[The opposition] owned life for a very long time. They owned family for a very long time. And I don’t think that anyone, regardless of your beliefs, will tell you that we as a society shouldn’t try to preserve family, or life. So they took it from us, right? And we let them take it.”

These lessons about morality are particularly impactful coming from extremely religious contexts, and where the Catholic church still has a lot of influence politically and socially. In Argentina, faith was also central to their successful campaign to legalize abortion. “80% of us consider ourselves Catholic,” says Giselle Carino, director/chief executive officer of Fòs Feminista, an international alliance for sexual and reproductive health, rights and justice. “So our faith was central to advancing our commitment to social justice, to avoiding suffering and to ensure that women can decide their future.”

“In Argentina, we start talking about women dying,” explains Guillen. “[The opposition was] forced to change and say ‘save the two lives.’ Talking about the life of the mother and the life of the fetus. We have not been afraid of using life.”

“It was claiming the very things that the anti-abortion people here claim, and they were winning that argument,” says Valladares about the Green Wave messaging. “It makes sense to me when you’re talking to other people who hold their religious values really close to their heart, and you’re hearing someone else who also does, you can relate to them.”

Adopt consistent visual branding like the green bandana

“So one of the first steps and it sounds simple, but it’s extremely powerful, was the use of the panuelo, (bandana)” says Guillen about the success of the Green Wave. “Why? Because a lot of the lack of cooperation comes from structures set up by donors. We are fighting for funding, who takes the credit, or which logos go into the event, right? Like how many conversations have we had about logos in our work? And the beauty about the panuelo is that anybody can print anything in the panuelo and anyone can write anything in the panuelo, but we are all united.”

Guillen also likes the bandanas because they don’t require institutional support or buy in. ”It also transformed the issue from being a completely institutional one to a street one. You don’t need to belong to an organization–everybody can have a panuelo.”

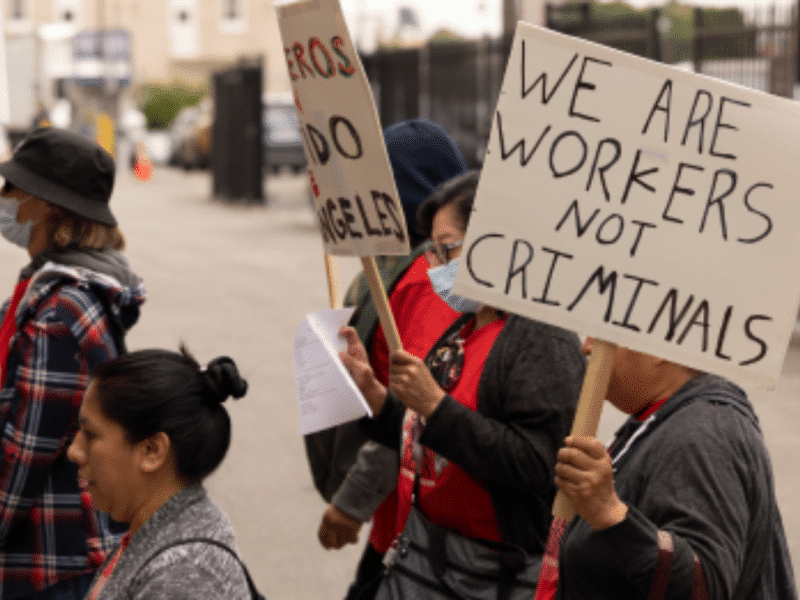

Groups in the U.S. are already starting to adopt the green bandana and other elements of the Latin American movement. NLIRJ recently put up billboards across Virginia with a green background similar to the Green Wave colors, and on a recent call about the Green Wave movement, the organizers wore green bandanas and talked about their collections from all over the world. Previously green had not been part of their organizational color palette.

The bandanas have also been showing up at marches across the U.S. “When I saw that for the first time in one of the marches in New York, my heart was melting,” says Carino. “I was so excited about that symbol of shared solidarity and shared existence. And then I saw it in Texas and in other in much more difficult places, and that gives me a lot of hope for the future. Green is the color of hope for us.”