In The Community

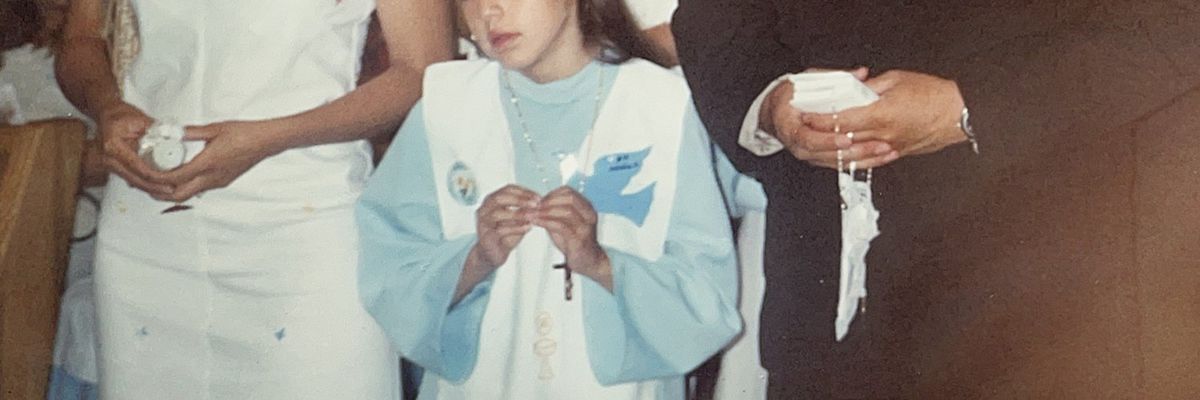

I was inducted into the Catholic faith pretty much straight out of the womb, starting off at this Catholic primary school in Mexico when I was just six years old. I was pure Play-Doh back then, ready to be shaped and molded. There I was, learning the Holy Bible like it was basic arithmetic or the ABCs.

Now, as a kid, you don't exactly have a whole laundry list of "sins" under your belt. Yet, we were herded to the confessional every week and prompted to confess our sins. Often, I'd be at a loss for what to say, and the priest would suggest things like: "Did you raise your voice at your parents? Did you disobey them? Did you think of something mean? That's a sin, too." So, there I was, scavenging through my memories for something, anything, to feel guilty about, confess, and beg forgiveness from God at the ripe age of six.

As I grew, I jumped through all the Catholic hoops. First communion, confirmation, even theology courses. The path to becoming an exemplary Catholic is indeed a long one. In time, I took on the role of a youth pastor, passing on the teachings ingrained in me since childhood to a younger generation of girls: respect and honor your parents unconditionally, remain a virgin until marriage, treat your body like a temple, and as a woman, be submissive and compliant to your man…

As I moved on to college and gained more independence from my parents and the environment I grew up in, I started to experiment with new experiences. Nothing outrageous, just typical teenage activities: flirting with boys, drinking, partying, and sometimes sneaking out on adventures my parents would never have approved of. It's ironic, really – the girls with the most conservative parents turn out to be the sneakiest of the lot. I should know.

But, looking back now, that time in my life feels more sad and uncomfortable than fun and exciting. I wanted to be a normal teen, but the guilt was always there, and boy, was it heavy. Every time I stepped out of line, I was sure God would punish me, perhaps by taking my parents away or making me fall ill. The looming "fear of God" that Catholics preach about became a literal terror for me.

When I first became sexually active, the accompanying guilt was overwhelming. No longer a virgin and unmarried, I felt like I'd let God down, disappointed my parents, and failed myself. Surely no man would want me anymore. I vividly remember crying about it constantly.

Fast forward a couple of years, and I found myself growing apart from the church. No big dramatic reason, just a general feeling of guilt and shame every time I was at church or with my youth group. Eventually, the guilt got so bad I just stopped going – I couldn't bear to be a hypocrite.

So, I distanced myself from it. And the more I walked away, the more I began to see the bigger picture. And it was ugly.

I realized I'd been taught since I was a kid to be perfect in every way – honor my parents, never swear or steal, keep my thoughts pure, avoid 'fake gods' like yoga or horoscopes, follow the rules blindly, never question your faith, always be obedient and submissive, and never try to grow or learn outside of God's teachings.

Love until it hurts. Real love is always painful and hurts: then it is real and pure.

— Mother Teresa

I was led to believe that love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, and endures all things. I was taught that love must hurt. That suffering leads to the purification of the soul. Between popular media bombarding young girls with depictions of unhealthy relationships and a very misguided interpretation of Catholic principles, I fell into very harmful relationships. I had been conditioned to accept this as the norm. After all, the señoras talked about staying with their cheating, abusive husbands. Because love endures all things, right?

Only in the past few years have I learned that there's a name for all these experiences I've been going through. And say what you want about that – some people think we're just making up names for things – but naming it validates your experience and makes it easier for others to share theirs; it helps us define and express this amorphous monster of a thing we've been dealing with for all these years.

The term "Catholic guilt" is widely recognized today to describe a particular feeling of remorse that arises from violating the moral standards ingrained through Catholic upbringing.

For Latina women, the manifestation of Catholic guilt is not merely a theological concept but a sociocultural phenomenon that extends beyond the church's walls and permeates daily life. It intertwines gender expectations, family relationships, community dynamics, and individual self-worth.

The cultural ideal of "marianismo" suggests that women must embody purity, virtue, submissiveness, and self-sacrifice, akin to the Virgin Mary. This ideal puts considerable pressure on Latina women to uphold these standards of morality and virtue. Deviating from these norms can evoke feelings of guilt rooted in both cultural and religious contexts—emotions that I haven't been able to shake off, even though I abandoned Catholicism more than 10 years ago.

Many Latina women often bear the burden of preserving the family's honor and moral standing. This responsibility can engender Catholic guilt associated with behaviors or thoughts that deviate from the church's teachings, such as premarital sex, divorce, abortion, or even questioning the religious doctrine itself. You must not waver in your faith.

I cannot stress enough how heavily the weight of Catholic guilt can influence a woman's self-perception. It can induce feelings of inadequacy due to the impossible task of upholding an idealized and frankly unattainable standard of morality and purity. Guilt can also play a role in a woman's struggle with her personal identity, particularly if she identifies as LGBTQ+, a status still stigmatized in both the Catholic Church and many Latine communities, sometimes leading to internalized homophobia.

This ever-present feeling of guilt can be detrimental to mental health, resulting in issues like anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. The fact is, many of us are introduced to the Catholic faith almost as soon as we are born, baptized, and sent to Sunday school. So these teachings and feelings of guilt become deeply rooted in our sense of being.

As we acknowledge these experiences, we empower ourselves and others to open up about their struggles and seek healing. It’s vital for mental health professionals to recognize and understand the nuances of Catholic guilt in Latina women, offering culturally competent care and support, yet not many do.

By recognizing and naming my experience, I've found it easier to share my story with other women who face similar struggles. My hope is that, through open conversations and mutual understanding, we can begin to break free from guilt, embrace our individuality, and respect our autonomy in making informed choices. Only then can we find the freedom to heal and redefine our relationships with faith, culture, and ourselves.

- Setting Healthy Boundaries with Family is Crucial for Latine Mental Health ›

- Machismo and Marianismo: What's the Difference? ›

- Self-Sacrifice in Latino Relationships - Luz Media ›

- 10 Tips to Create Better Mental Health Habits as Latinos ›

- How We Talk About Mental Health as Latinos Needs to Change - Luz Media ›

- The Dark Side of Black Friday: 10 Reasons to Skip It - Luz Media ›

Mother’s Day is a day meant to honor and celebrate the special bond we share with our mothers or mother figures. The holiday is celebrated on the second Sunday of May in the U.S. and in some Latin American countries, like Cuba, Chile, Colombia, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, Honduras, and Venezuela. However, some Latina mothers celebrate the holiday twice, depending on where they’re from. For example, mothers of Mexican, Guatemalan, or Salvadoran descent will also observe Mother’s Day on May 10, so it’s a double celebration for them. Argentina, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Paraguay, and Panama have their own dates as well.

Usually, Mother’s Day is all about connecting with our mothers and pampering them throughout the day. For many Latina daughters, though, it’s not a happy occasion. Mother’s Day can be very complicated when your relationship with your mother is not a healthy one and you’ve made the decision to break or diminish ties with her. That’s the reality for many Latinas who have prioritized their own mental health and well-being by creating solid boundaries.

Marianismo often plays a role in difficult mother-daughter relationships. Rooted in Christianity, or rather the Roman Catholic beliefs the Spanish indoctrinated their newly conquered native subjects with during colonialism, marianismo is the other side of machismo. It defines gender-based expectations for Latin American women and it’s deeply ingrained in Latino culture. It’s because of marianismo that Latina women are taught from a young age that they have to be submissive, self-sacrificing, and pure. In other words, they have to be quiet instead of loud, weak instead of strong and are consistently discouraged from being independent, sexual, opinionated, and a host of other empowered traits.

@therapylux #marianismo #machismo #latinxtiktok #latinxmentalhealth #latinas

The idea behind marianismo is to be more like the Virgin Mary, a figure that’s considered to be the epitome of purity and goodness. Whether the messaging is subtle or explicit, marianismo in the Latino household imposes a narrow concept of what it means to be a woman and it reinforces powerlessness. It’s important to note that marianismo is not a burden every Latina carries, but many of them do.

In Latin American countries, society helps reinforce marianismo. In the U.S., things are slightly different, which is why first-generation immigrants break away from it more effectively. But this sometimes also means breaking away from their mothers, who often refuse to confront their harmful marianismo beliefs.

There’s no denying that the mother-daughter bond is one of the most important in a woman’s life. For Latinas in particular, mothers are highly influential figures in our lives. But what if your relationship with your mother is toxic and complicated? In Latino culture, it’s taboo to say anything negative about our mothers. Being critical of them means you’re “ungrateful,” but the truth is that some mothers fail their daughters. Especially in helping them foster an independent sense of self. Some mothers want their daughters to be a certain way instead of allowing them to be their own person, which is why they’re often critical and overly demanding.

@santamykah and that’s on being salty bc I’m daring to experiment, heal, and get to know myself at the age she was already raising 3 kids w a man she never loved 😗#toxic #toxicmom #healing #latina #firstgen #mentalhealth

Many Latinas have grown up with mothers who are too comfortable pointing out their flaws or dictating how they should be or act. This leads to constant opposition and a constant struggle to just be yourself. It makes many Latina daughters feel that who they are at their core is not good enough and fosters self-doubt at a level that affects everything else in their lives. Even as adults, we want our mothers to approve of us and love us for who we are, but there comes a time when enough is enough. There’s only so much toxic criticism one can take.

This is what leads many Latina daughters to cut ties with their mothers, however painful that may be. Needless to say, estrangement is frowned upon in the Latino community because we place a lot of value on family. “It doesn’t matter what we do to each other, at the end of the day, we’re family.” That’s the kind of mindset most Latinos have, but it’s neither healthy nor realistic. The way we treat each other matters and being related doesn’t mean we can get away with harmful behavior.

@latinxestrangement #latinxcommunity #marianismo #familyestrangement #latinos

In general, estrangement is seen as extreme and as a problem in itself. However, for many, estrangement is the solution and the relief they’ve been searching for. Make no mistake, the dilemma Latina daughters are often faced with is unsolvable. Choosing between having a relationship with your mother and doing what’s best for your own life isn’t as easy as it seems. However, it’s often the only thing left to do after you’ve tried everything else to have a better relationship with your mother.

There comes a point where you’re better off without them in your life. That’s a harsh truth to face because, even if estrangement is what’s best for you, you both lose something. But for many Latinas, that loss is a new beginning. It’s a weight lifted off their shoulders and a deep sigh of relief. It’s sad and tragic that it has to end that way, but it’s better than the alternative of maintaining that toxic mother-daughter relationship.

@nicolerodriguez94 Normalicemos alejarnos de nuestras familias, renunciar a ellos esta bien por nuestra salud mental, ahora estoy sanando ❤️🩹#greenscreen #saludmental #familiastoxicas #madretoxica #parati #fyp

On a larger scale, estrangement can help the Latino culture heal in the long term. Setting boundaries with our families, which isn’t something we’re encouraged to do in the Latino community, means we’re no longer letting abuse slide. The romanticization of family bonds and self-sacrifice doesn’t have the same hold. Rejecting that romanticization and rejecting marianismo is a way to help break the cycle.

Intergenerational emotional and psychological abuse has to be confronted and, sometimes, extreme measures are the only way to help the older generation face their harmful beliefs and values, and reframe what needs to be reframed. Setting boundaries is a shock to the system; a shock that lets our mothers and everyone else in our families know what kind of behavior isn’t acceptable anymore and never should’ve been in the first place. After that, the ball is in their court. They can either adapt or lose the privilege of being a part of your life.

While, for some, Mother’s Day is a celebration of the bonds they share with their mothers, for others, it’s a reminder of the breaking of those bonds. Whatever side you’re on, remember that love and respect is a two-way street.

- Encanto: The Authentic Struggles Faced by Latina Daughters ›

- Is Self-sacrifice a Love Language in the Latine Community? ›

- Latino Family Dynamics: The Importance of Setting Boundaries ›

- Top 10 Things Latina Family Matriarchs Should Stop Doing - Luz Media ›

Experts in science and mental health have consistently shown that a person's mental well-being is largely shaped by their environment, lifestyle, and other factors. Beyond this, there are deeply ingrained social constructs rooted in cultural norms, such as machismo and marianismo. While many might be familiar with the concept of "machismo," "marianismo" might be less understood. How do they differ?

It's important to know that a person's mental health can be significantly influenced by these factors, especially within the Latine community, where mental health is still a topic shrouded in stigma. Both machismo and marianismo, although different, can contribute to negative mental health outcomes for individuals within the Latine community. These cultural norms not only perpetuate harmful beliefs and behaviors but also lead to societal shaming of those who attempt to break away and challenge these detrimental patterns.

What is machismo and marianismo?

Photo by Fa Barboza on Unsplash

Photo by Fa Barboza on UnsplashMachismo is a social construct that promotes exaggerated masculinity, or the traits that are often attributed to masculinity, such as dominance and aggression. Machismo is also an ideology that deems women inferior to men and promotes the denial of women from participating in work or lifestyles that are associated with power or independence in any way. This can include everyday behaviors such as the ability to drive a car or manage money. It promotes the marginalization of women and, in doing so, ultimately harms men themselves.

Machismo is often preceded by marianismo, a term we don't hear about as often, but that plays a role in the execution of machismo as a belief system within society and, more specifically, Latino culture.

Marianismo is a twisted perception of the female gender as a one-dimensional being with specific characteristics often attributed to feminity, such as self-sacrifice, sexual purity, taking care of others, morality, subordination, and self-silencing.

Connected with both machismo beliefs and those of the Roman Catholic Church, marianismo also promotes the idea that women are spiritually superior to men and should therefore be a pillar of spiritual strength within the family. Furthermore, it leads to the belief that seeking help from a mental health professional goes against religion as there's difficulty secularizing human needs from religious convictions.

Political Scientist Evelyn P. Stevens wrote an essay on the subject. She points out that sometimes, women cling to this role and continue to teach machismo ideals to their sons, daughters, grandchildren, etc. While this may be more of a generalized take, as Latina women have certainly evolved, we can't deny that we still see these behaviors in modern society.

How do machismo and marianismo impact mental health?

Photo by Joice Kelly on Unsplash

Photo by Joice Kelly on UnsplashSo, how are machismo and marianismo directly related to poor mental health in the Latino community? Both of these systems promote ideas that put a human being into a box or pedestal that's hard to get out of.

For machismo, the idea that a man should be "stronger" both mentally and physically makes it hard to express emotions and, furthermore, accept the need for help and vocalize it. Marianismo, on the other hand, promotes the acceptance of toxic behaviors from the woman's side.

When put side by side, it's as simple as a man that believes they can and should assert power over women either physically or emotionally, who will more often than not use that power to harm them. A woman with a marianismo belief system will believe they need to accept this behavior, which will result in emotional manipulation, physical abuse, anxiety, depression, or even suicide on both parts.

This study by the US National System of Health revealed that "specific components of machismo and marianismo were associated with higher levels of negative cognitions and emotions after adjusting for socio-demographic factors."How does it affect people through various developmental processes?

Photo by Sebastián León Prado on Unsplash

Photo by Sebastián León Prado on UnsplashFrom the early stages of development, when their parents or caregivers teach a child different behaviors and beliefs, a child can be affected by machismo and marianismo, both from learned behaviors (seeing how the member of their family interact) and from directly being taught these ideologies. We often see this happen in our community when a boy is told, "don't cry, boys don't cry," or when a girl is told, "don't be too loud," "be a lady."

And as these children grow into teenagers and young adults, it turns into "it's normal for him to get angry and get into fights, boys will be boys" and "that skirt is too short, go change." These children turn into active members of society when they turn into adults, and they can either continue to perpetuate these ideologies or fight against them, regardless, the harmful impact on their mental health is made, and they must now actively try to better themselves by seeking professional help and breaking toxic cycles.

What can we do to take action against machismo and marianismo?

We have to be aware and shine a light on these issues, educating ourselves and then our families so that toxic generational cycles can be broken and mental health can finally be destigmatized in the Latine community. It is important to promote mental health so that our loved ones and other members of the community don't have to suffer in silence

Mental Health Resources

This article, created by Mental Health America, will navigate through various statistics, learning material, and resources to seek professional help. Here are a few of the many you will find:

- Therapy for Latinx: national mental health resource for the Latine community; provides resources for the Latine community to heal, thrive, and become advocates for their own mental health.Therapist Directory

- Latinx Therapy: breaking the stigma of mental health related to the Latine community; learn self-help techniques, how to support self & others.

- The Focus on You: self-care, mental health, and inspirational blog run by a Latina therapist.

If you or somebody you know is thinking about suicide or is in severe emotional distress, please contact:

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- Call 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255)

- Use the online Lifeline Crisis Chat

Both are free and confidential. You’ll be connected to a skilled, trained counselor in your area.

For more information, visit the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

You can also connect 24/7 to a crisis counselor by texting the Crisis Text or texting HOME to 741741.

- Are You Normalizing Machismo in Your Everyday Life? ›

- Can Latino Fathers Redefine Masculinity and Overcome Machismo? ›

- Why is it Socially Acceptable for Men, but not Women, to Hold Onto Childhood Interests? - Luz Media ›

- Is Your Behavior Machista? Probably. - Luz Media ›

- Does Emotional Manipulation Lurk within Our Family? - Luz Media ›

- What's in a Name? Hispanic, Latino, and More Explained - Luz Media ›

- Archaic Holiday Family Party Questions: A Modern Latina's Guide - Luz Media ›

- Understanding Weaponized Incompetence - Luz Media ›

- 10 Signs That Man You’re Considering Dating is Machista - Luz Media ›

- How Catholic Guilt Shaped My Life - Luz Media ›

- How We Talk About Mental Health as Latinos Needs to Change - Luz Media ›